The House Agriculture Committee unveiled a draft farm bill Friday that would revamp a key international food aid program, boost risk management options for specialty crop growers and nullify California's…

Focus on SNAP, the Largest Farm Bill Program

Today’s update looks briefly at the SNAP (food stamps) program within the Farm Bill. The USDA’s Economic Research Service (ERS) released a report on Thursday that examined the program in detail. This update looks at core points from the ERS report with particular focus on issues relating to “block granting” the program to States, and program work requirements.

Background

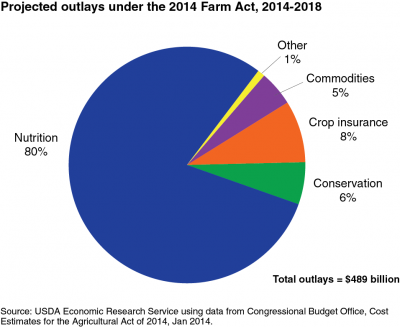

The Economic Research Service has noted that, “The Agricultural Act of 2014 (2014 Farm Bill) is made up of 12 titles governing a wide range of food- and agriculture-related policy areas. The Congressional Budget Office (CBO) projected that the total cost of the new Farm Bill would be $489 billion over 5 years (2014-2018). Nutrition programs account for about 80 percent of this total, with projected outlays for crop insurance, conservation, and commodities representing another 19 percent.”

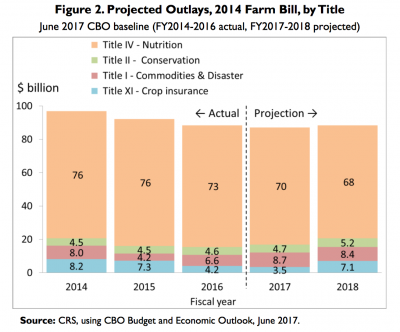

However, the Congressional Research Service pointed out in October that, “[The CBO] has updated its projections of government spending based on new information about the economy and program participation. Outlays for FY2014 to FY2016 have become final, and updated projections for FY2017 and FY2018 reflect lower farm commodity prices and lower costs for SNAP. The new five-year estimated cost of the 2014 farm bill, as of June 2017, is now $453 billion for the four largest titles, compared with $484 billion for those same titles three years ago. This is $31 billion less than what was projected at enactment.”

From a political standpoint, nutrition programs, and in particular the SNAP program, have become a flashpoint for sharp disagreements in the past. A farmdoc daily article just after the election in November 2016 reminded readers that, “During the previous [Farm Bill] effort, moreover, the House was the scene of a very bitter partisan debate over SNAP that resulted in the farm bill’s initial defeat on the House floor. Much of that controversy involved work requirements and splitting SNAP from the rest of the bill.”

Back in September, the Senate Ag Committee held a hearing that focused on fraud in the SNAP program, and specifically highlighted program payment error rates and misreporting of program costs by some states. In June, the House Agriculture Subcommittee on Nutrition held a hearing to evaluate technology and modernization of the SNAP program. And earlier this month, a news article noted that, [House Ag Committee Ranking Member Collin Peterson (D., Minn.)] spoke in an interview last week about his hopes for the spending package, and fears that ideological fights over food stamps could derail the bill this time around.”

SNAP- Recent Analysis From USDA’s Economic Research Service

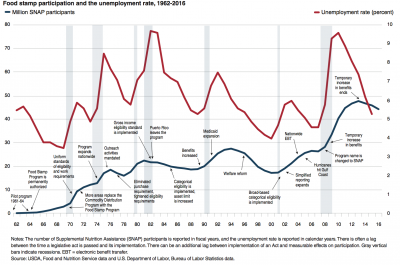

With this background in mind, ERS released a report on Thursday (“Design Issues in USDA’s Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program: Looking Ahead by Looking Back,” by Victor Oliveira, Mark Prell, Laura Tiehen, and David Smallwood), which stated that, “The [SNAP] program affects the lives of many Americans: on average, about 14 percent of the Nation’s population participated in the program each month in fiscal year (FY) 2016.

As one of the mainstays of the country’s safety net, the program accounts for over half of USDA’s annual budget.

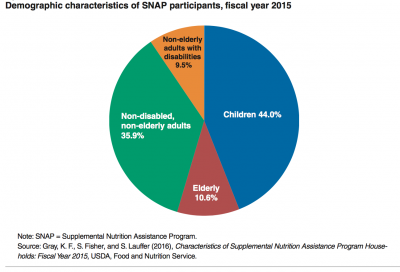

The ERS report indicated that, “In FY 2015, children, elderly, and nonelderly adults with disabilities composed 64 percent of all SNAP participants, and their households received 60 percent of SNAP benefits.”

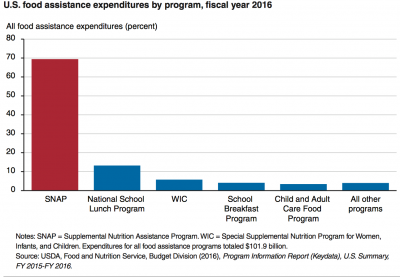

“In FY 2015, an estimated 32 percent of SNAP households had earned income,” the report said, while adding that, “SNAP is the cornerstone of the Nation’s food assistance programs, accounting for 69 percent of all Federal food assistance spending in FY 2016.”

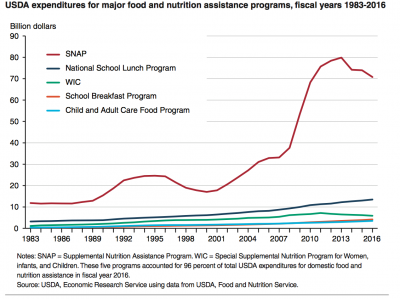

Last week’s report also pointed out that, “While expenditures of most other food and nutrition assistance programs have generally steadily increased in the last three decades, SNAP expenditures have fluctuated widely.”

With respect to work requirements, ERS pointed out that, “Adults ages 16 through 59 must register for work, accept suitable employment, and not voluntarily quit a job or reduce job hours—or alternatively, they must take part in workfare (unpaid work through a special State-approved program) or an employment and training program if they are referred by the local office.”

There are several exemptions to these requirements; and, “Generally, nondisabled adults ages 18 through 49 who do not have any dependents (referred to as able-bodied adults without dependents, or ABAWDs) can receive SNAP benefits for only 3 months in a 36-month period if they do not work or participate in a work training program at least 20 hours per week or participate in workfare.”

After providing a very interesting and easy to read history of the SNAP program, the ERS report examined several current issues relating to the program including: Block granting SNAP; limiting the types of food participants can purchase; store eligibility requirements; adequacy of SNAP benefits; program access; and, work requirements.

Issues in the report relating to block granting the program and work requirements are highlighted in more detail.

SNAP- Block Grant Issues

The ERS economists stated that, “It was not until 1971 that the Federal Government curbed State flexibility by establishing uniform national standards of eligibility based on income and asset limits…However, beginning in 2000, States once again received increased flexibility to modify eligibility requirements to make the program more accessible and to simplify and streamline program administration.”

“The term block grant typically refers to a fixed amount of funding that the Federal Government provides to a State—thus ending the program’s entitlement status—and in return, the State takes on responsibility for the program. Under a block grant, the State pays none of the program’s cost up to the amount of the block grant, and then pays 100 percent of any additional cost. Because decisions on SNAP program design and operations would devolve to the States, eligibility standards and benefit levels could vary across States under a block grant. In recently proposing converting SNAP to a ‘State Flexibility Fund,’ which would operate as a block grant, the U.S. House of Representatives emphasized that it considered State-level exibility to be a desirable feature of block grants.”

The report indicated that,

A key argument of the House Budget Committee in favor of block granting SNAP is that it would give States the opportunity to come up with innovative approaches to design their program to best address their specific needs and circumstances

“Cost savings can emerge under blocking granting because the cap on Federal spending dampens States’ incentives to increase SNAP caseloads and expenditures.”

The ERS report explored arguments against block granting SNAP and stated that, “The first argument focuses on house-hold-level well-being. Eliminating the program’s entitlement status through a block grant undermines its ability to respond quickly to increased need—for example, during an economic downturn. As a Federal entitlement, SNAP provides benefits automatically to all who meet eligibility standards. Under block granting, Federal funding levels are usually considered to be fixed so that during an economic downturn when the need for assistance increases, per-household benefit levels would have to be reduced or people would have to be cut from the rolls, thereby potentially increasing the prevalence of hunger in this country.”

SNAP- Work Requirement Issues

Wall Street Journal writer Jesse Newman reported on Thursday that, “Agriculture Secretary Sonny Perdue wants more food-stamp recipients to work for that assistance, an opening salvo in what are expected to be contentious negotiations this year over the next U.S. farm bill.”

Ms. Newman explained that, “During a tour through Pennsylvania on Wednesday, Mr. Perdue said tightening work requirements for recipients of the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program, or SNAP, is one of the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s priorities for the coming bill.

“‘We have to figure out ways to feed the poorest in our society more productively and help them learn to transition into an independent lifestyle,’ Mr. Perdue told Pennsylvania dairy farmers.”

At @centralpafb talking about American agricultural abundance and efforts to help feed people in need. In our #FarmBill principles, we also support work toward self-sufficiency for those receiving supplemental assistance.

— Sec. Sonny Perdue (@SecretarySonny) January 24, 2018

Principles: https://t.co/MFH0hF8Pz4 pic.twitter.com/Nqimu1AEAo

And Bloomberg writer Alan Bjerga reported on Wednesday that, “Senate Agriculture Committee Chairman Pat Roberts, a Kansas Republican who has raised concern about fraud in the SNAP program, said that while some food stamp rules may be tightened, changes to the program aren’t likely to be dramatic, given a need to attract Democratic votes in the Senate. Perdue, in the interview last week, also said the administration wouldn’t be pushing for radical change to the program.”

While addressing work requirement issues, the ERS report noted that, “In FY 2015, almost two-thirds (64 percent) of SNAP participants were children, elderly, or non- elderly adults with disabilities.

Thus, only a minority of SNAP participants are expected to comply with the general work requirements, so the potential effects of work requirements on participation rates may be limited.

“Many adults without children in the household do work. At least a quarter of households with such adults work while receiving SNAP, and about 75 percent work in the year before or the year after receiving SNAP. The finding that people are more likely to be employed before they enroll in SNAP and after they leave the program (than while enrolled in SNAP) suggests that the program functions as a temporary safety net for the working poor. In addition, some SNAP participants are employed even though they are exempt from the general work requirements. Altogether, in an average month of FY 2015, an estimated 32 percent of all SNAP households had earnings from work.”