Farm Progress' Joshua Baethge reported at the end of last week that "it’s hard to find anyone optimistic about passing a new farm bill this year. While the two political…

An Overview of Crop Insurance: Recent Congressional Research Service Report

Earlier this month, the Congressional Research Service (CRS) released a report titled, “Federal Crop Insurance: Program Overview for the 115th Congress.” Today’s update focuses on key highlights from the CRS report.

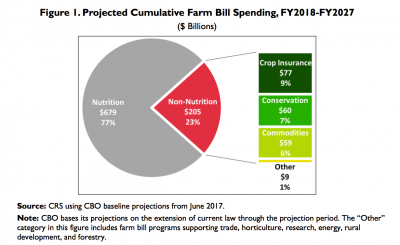

The CRS report explained that, “From 2007 to 2016, the federal crop insurance title had the second-largest outlays in the farm bill after nutrition. The total net cost of the program during those years was about $72 billion. For FY2018 through FY2027, the Congressional Budget Office (CBO) projects that crop insurance will continue to be the second-largest farm bill outlay after nutrition, averaging about $7.7 billion a year, assuming current law remains in effect (Figure 1).”

Importantly, the CRS update noted that,

The federal crop insurance program is permanently authorized (7 U.S.C. §1501 et seq.) and receives mandatory funding. As such, it would continue to operate in the event that Congress does not enact a new farm bill, although farm bills have been vehicles for modifying the program in the past.

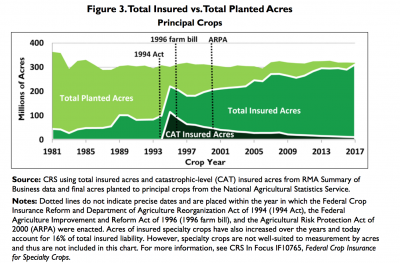

After describing several of the challenges faced by early crop insurance providers, and including valuable historic perspective on the development of the modern federal crop insurance program, the report stated, “Between 1980 and 2015, acres enrolled in crop insurance grew from 26.6 million acres (12% of eligible acres) to about 238 million acres (86% of all acres), excluding hay, pasture, range, and forage and separately livestock and nurseries. During that time frame, the number of crops insured increased from 28 to 123. The types of policies offered also increased over this period from one—yield insurance—to over 20, including yield, revenue, margin, and whole farm revenue, among others.”

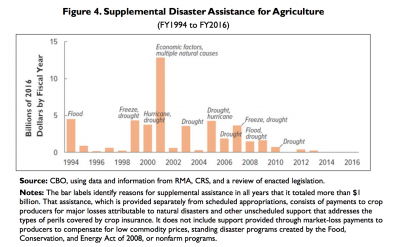

The CRS report also indicated that, “According to CBO, one of the stated policy goals of federal crop insurance has been to reduce the agricultural sector’s reliance on supplemental or ‘ad hoc’ disaster assistance payments. However, it is difficult to assess whether this policy goal has been achieved. According to CBO ‘it is not possible to compare federal spending on the crop insurance program with spending on supplemental assistance that might have been provided in its absence, nor are data available with which to measure declines in federal assistance resulting from increases in spending on the crop insurance program.'”

For perspective on the importance of federal crop insurance, CRS stated,

Since the Agricultural Act of 2014 (‘2014 farm bill,’ P.L. 113-79), the federal crop insurance program has become a central agricultural support program, with comparable or larger outlays than either commodity price and income support programs (e.g., Agricultural Risk Coverage, Price Loss Coverage, and Marketing Assistance Loans) or conservation programs (e.g., Environmental Quality Incentives Program, Conservation Stewardship Program, and Conservation Reserve Program).

More narrowly, this month’s update also noted that, “During the 2000-2016 period, the four largest crops produced in the United States—corn, soybeans, wheat, and cotton—accounted for about 75% of the enrolled acreage and 80% of the claims paid.”

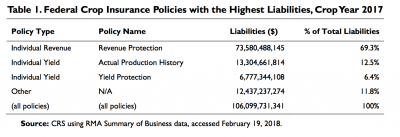

In addition, the report included a table which displayed “the top three policies by liability in crop year 2017,” which included: (1) Revenue Protection, (2) Actual Production History, and (3) Yield Protection. “Together these three policies accounted for approximately 88% of total liabilities in the federal crop insurance program.”

Meanwhile, the CRS update stated that,

Unlike some farm subsidy programs, federal crop insurance does not limit subsidy or indemnity amounts per individual or entity, nor does it restrict eligibility based on adjusted gross income.

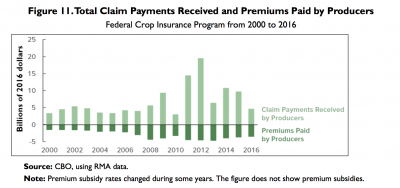

With respect to indemnity payments, the CRS report explained that, “From 2000 to 2016, producers received $65 billion more in claim payments than they paid in premiums. In other words, during this period an average producer received an average of $2.22 in claim payments for each dollar paid in crop insurance premiums. Not every producer experienced a net positive return from purchasing crop insurance, and some received more than the calculated average.”

Concluding, CRS noted, “The federal crop insurance program is a central part of federal support for agriculture. Given the program’s significant cost and share of USDA program outlays, it is a frequent target for budgetary savings.”