A prolonged military conflict in the Middle East could potentially upend key commodity markets due to Iran’s control of the Strait of Hormuz, one of the world’s most important trade…

Despite Ample Global Supplies, Concerns About “Food Nationalism,” and Supply Chain Restrictions Amid COVID-19 Outbreak

Earlier this week, Bloomberg writers Isis Almeida and Agnieszka de Sousa reported that, “It’s not just grocery shoppers who are hoarding pantry staples. Some governments are moving to secure domestic food supplies during the conoravirus pandemic.”

The Bloomberg article noted that, “To be perfectly clear, there have been just a handful of moves and no sure signs that much more is on the horizon. Still, what’s been happening has raised a question: Is this the start of a wave of food nationalism that will further disrupt supply chains and trade flows?”

Though food supplies are ample, logistical hurdles are making it harder to get products where they need to be as the coronavirus unleashes unprecedented measures, panic buying and the threat of labor crunches.

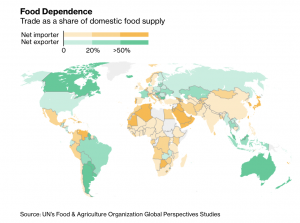

“As governments take nationalistic approaches, they risk disrupting an international system that has become increasingly interconnected in recent decades,” the Bloomberg article said.

The Bloomberg article pointed out that, “Unlike previous periods of rampant food inflation, global inventories of staple crops like corn, wheat, soybeans and rice are plentiful, said Dan Kowalski, vice president of research at CoBank, a $145 billion lender to the agriculture industry, adding he doesn’t expect ‘dramatic’ gains for prices now.”

And Reuters writers Naveen Thukral and Maha El Dahan reported on Thursday that, “Global food security concerns are mounting as some governments contemplate restricting the flow of staple foods with around a fifth of the world’s population under lockdown to fight the widening coronavirus pandemic.”

The erratic nature of consumer buying is stoking concern that some governments are moving to stem the flow of food staples to ensure their own populations have enough while supply chains are disrupted by the pandemic.

On Friday, Reuters writer Polina Devitt reported that, “Russia’s Agriculture Ministry said on Friday it had proposed setting up a quota for Russian grain exports at 7 million tonnes for April-June.

“This measure, if approved by the government, would cover the main grain types, including wheat, rye, barley and corn. It would help ensure the stability in the domestic food market, the ministry said in its statement.”

For more details on country export restrictions, see this summary from Reuters News: “FACTBOX- Trade restrictions on food exports due to coronavirus pandemic.”

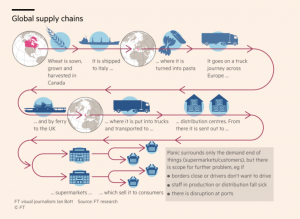

In more detailed reporting on logistical fault lines, Financial Times writers Emiko Terazono and Judith Evans reported this week that, “Following the journey of pasta from farm to fork illustrates all the processes that will need to be kept running during the coronavirus outbreak. Like many foodstuffs, pasta relies on a highly complex international supply chain — often passing through several countries on the way to consumers’ plates.

“For pasta eaten in the UK, most is made from wheat shipped from Canada, which is then processed by companies such as Barilla and De Cecco in Italy, which exported $3bn of pasta last year. After being transported by trucks through Europe, UK wholesale distributors, such as Princes, will then sell it on to supermarkets.

“Wheat production itself should be relatively unaffected by the coronavirus. In Canada, grain production and harvesting is largely mechanical.”

The FT writers stated that, “Even if production can be maintained in Italy, however, analysts warn there may be further disruption ahead if border controls clog motorways, deterring drivers from delivering products. ‘Food is a priority and things should be moving freely, but no one wants to get caught up in a line of 1,000 trucks,’ said Stefan Vogel, analyst at Rabobank.

“Governments are also stocking up on staples, with countries including Algeria and Turkey issuing new tenders for wheat, while Kazakhstan has stopped exports of food including onions and buckwheat.”

Also with respect to transportation and logistics, Laurence Norman and Drew Hinshaw reported on Friday at The Wall Street Journal Online that, “The European Union, the world’s second-largest economy, was built on free movement of people and goods. For three decades, Europe’s internal market flourished as the bloc expanded and borders fell, bolstering growth. Businesses grew to depend on deeply integrated supply chains and workers who ignore national demarcations inside the bloc.

“Coronavirus has suspended that model, upending commerce and communities. Road-travel restrictions, some imposed unilaterally as the pandemic hit this month, combined with grounded air transport, threaten companies’ ability to produce and deliver vital goods and services, including food, medicine and pesticides, as well as medical care.”

“Officials fear that if border restrictions linger as the virus fades and commerce resumes, the blockages will cripple Europe’s economic recovery,” the Journal article said.

Meanwhile, Bloomberg writer Megan Durisin reported on Thursday that, “Consumers may be hoarding staples like flour and bread amid the coronavirus crisis, but once the panic buying ends, the world will probably still have a huge stash of wheat.

“That’s according to the International Grains Council, which left its projection for this season’s wheat stockpiles unchanged despite a surge in consumer demand. Because farmers should be able to complete plantings as planned, the upcoming harvest will increase and push inventories up about 3% to a record 283 million tons next season.”

Even though world #wheat inventories are tentatively projected to increase y/y, the rise is attributed entirely to gains in China and India, with stocks in major exporters posting another decline. pic.twitter.com/dLb04tT0hE

— International Grains Council (@IGCgrains) March 26, 2020

“The IGC warned the outlook may change once the pandemic’s duration is better known. Plus, the increase in wheat stockpiles is being driven by China and India, which don’t typically supply other nations. Inventories of all grains, including crops like corn and barley, will remain little changed next season.”

Amid tightening in China, global #maize (#corn) ending stocks in 2020/21 are expected to recede to their lowest since 2012/13. However, due to an accumulation in the US, inventories in the four main exporters could rebound to a four-season high. pic.twitter.com/Cbs745GuS9

— International Grains Council (@IGCgrains) March 26, 2020

Also this week, Reuters writers Hallie Gu and Naveen Thukral reported that, “Chinese soybean processors fear the spread of coronavirus in major exporters could lead to further supply shortages, with some plants in the world’s biggest buyer already having to wind back operations, industry sources and traders said.

Top producers Brazil and Argentina have warned of possible delays in getting beans to ports because of transport and other restrictions to control the virus. The moves come after delayed shipments from Brazil due to rains in late February have slashed Chinese inventories to record lows.

The Reuters writers explained that, “‘Shipping from port to port is not an issue, but the problem is getting soybean supplies to ports by trucks,’ said one Singapore-based grains trader, referring to Brazil.

Shipments of #soybean to China in the first five months of 2019/20 (Oct/Sep) were up 8% y/y. While crushing plants were disrupted by the coronavirus outbreak, full-year imports are still seen rising 2% y/y, with heavy purchases from Brazil likely in coming months. pic.twitter.com/RqKp581CnH

— International Grains Council (@IGCgrains) March 27, 2020

“Benchmark Chicago soybean futures have risen nearly 2% this week, rising for a second week in a row, although globally there is no shortage of soybeans, with Brazil producing a record crop.”