A prolonged military conflict in the Middle East could potentially upend key commodity markets due to Iran’s control of the Strait of Hormuz, one of the world’s most important trade…

During COVID-19 Outbreak, Some Countries Restrict Ag Exports– WTO / UN Stress Importance of Keeping Supply Chains Open

Wall Street Journal writers Kirk Maltais and Joe Wallace reported this week that, “Consumers are loading up on pasta, rice and bread. Farm supply lines are disrupted. Countries are restricting agricultural exports.

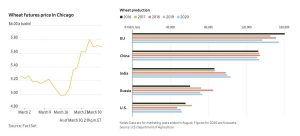

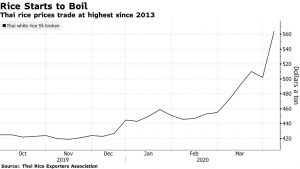

The result: Prices of wheat and rice, two of the world’s staple grains, are rising sharply. Difficulties moving grain within countries and across borders, coupled with frenzied buying, could exacerbate the impact of the pandemic on the global food market.

“The price of wheat futures trading in Chicago, the global benchmark, has risen 15% since mid-March and reached as high as $5.72 a bushel Monday, bucking the coronavirus-induced economic downturn that has hurt most commodity markets.”

The Journal article stated that, “The United Nations’ Food and Agriculture Organization says logistical issues, along with the falling value of emerging-market currencies, are conspiring to make grains more expensive for food-importing nations. That has the potential to create a food crisis in poorer countries, as well as regions hit hard by the pandemic.”

The Journal writers added that, “To be sure, the world isn’t about to run out of food…But getting it to the right places is proving a problem.”

Meanwhile, Reuters News reported this week that, “Kazakhstan will introduce quotas on its exports of wheat and flour and lift the ban on flour exports introduced this month to ensure steady domestic supply amid the coronavirus crisis, the Kazakh Agriculture Ministry said on Monday.”

And on Tuesday, Reuters News reported that, “The government has yet to approve the agriculture ministry’s proposal to limit Russian grain exports to 7 million tonnes from April through June, but the economy ministry said on Monday it backed the idea.”

Bloomberg writer Heesu Lee reported this week that, “Russia, Kazakhstan and Ukraine have already announced plans to limit wheat exports, and in Asia worries over making sure there’s enough food for everyone have now spread to rice, the main staple for billions of people in the region. China and India are the biggest global producers and consumers.”

The Bloomberg article pointed out that, “The reality is that there is no actual shortage. Warehouses in India, the world’s largest exporter, are brimming over with rice and wheat on record harvests. Global production of milled rice is estimated at around a record 500 million tons in 2019-20 and global stockpiles are at an all-time high of more than 180 million tons, according to the U.S. Department of Agriculture.”

In response to some of these restrictions, Reuters writer Stephanie Nebehay reported this week that, “Food supply chains must be protected from any trade-related measures taken during the COVID-19 pandemic, the heads of the World Trade Organization (WTO) and U.N. food and health agencies said on Tuesday, warning of possible shortages and price spikes.

“They voiced concern that disruptions to the movement of agricultural and food industry workers or food containers could result in the spoilage of perishables and increasing food waste and said protectionism was also a risk.

‘Uncertainty about food availability can spark a wave of export restrictions, creating a shortage on the global market,’ WTO director-general Roberto Azevedo, and the heads of the World Health Organization Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus and the U.N.’s Food and Agriculture Organization Qu Dongyu said.

And Clara Ferreira Marques pointed out this week in a Bloomberg Opinion column that, “In much of the world, preemptive policies can keep things moving. China’s Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Affairs, for example, brought in incentives for sowing and mechanization in early February, as well as support for livestock farming, and ‘green channels’ to help the movement of feed, breeding animals and produce. Governments can encourage trade, rather than nation-level hoarding. As the virus spreads, wealthier countries may also need to support developing ones, especially those hit by elevated import bills and weakened currencies.

“Disruptions will be inevitable. A global food crisis doesn’t have to be.”

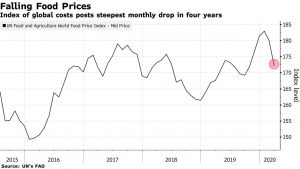

With respect to global food prices, Bloomberg writers Agnieszka de Sousa and Megan Durisin reported on Thursday that, “The global economic slowdown is causing the biggest drop in food prices since 2015 as demand shrinks for everything from dairy to sugar.

“The FAO Food Price Index, a global gauge of prices, dropped 4.3% in March, the United Nations’ Food & Agriculture Organization said Thursday. That’s the steepest decline since August 2015. Food costs fell as government restrictions on freedom of movement exacerbated demand destruction for oil, which pressures biofuels consumption. Biofuels are a key source of demand for sugar and vegetable oils.

“‘The price drops are largely driven by demand factors, not supply, and the demand factors are influenced by ever-more deteriorating economic prospects,’ FAO Senior Economist Abdolreza Abbassian said in a statement.”

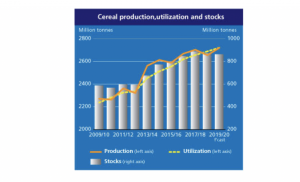

Separately on Thursday, the FAO released its Cereal Supply and Demand Brief, which stated that, “Global cereal markets are expected to remain balanced and comfortable despite worries over the impacts of COVID-19. While localized disruptions, largely due to logistical issues, pose challenges to food supply chains in some markets, their anticipated duration and magnitude are unlikely to have a significant effect on global food markets.”

The FAO Brief added that, “FAO’s estimate for 2019 world cereal production has been revised upward by 1.2 million tonnes this month, and now stands at 2 721 million tonnes, surpassing the 2018 global output by 64.6 million tonnes (2.4 percent).”

In other news regarding COVID-19 and the movement of agricultural commodities, Reuters writers Hugh Bronstein and Maximilian Heath reported this week that, “Argentine shipments of soymeal, soybeans, corn and other agricultural exports were delayed as the government ramps up inspections of incoming cargo ships to ensure crew members were free of coronavirus, industry sources said on Monday.

“While Argentine growers were harvesting Southern Hemisphere fall crops unimpeded by health measures taken against the pandemic, supply from the world’s biggest exporter of soymeal livestock feed was slowed as some municipal authorities refused to let grains trucks drive through their jurisdictions.”

And Reuters writer Jake Spring reported this week that, “China has not approved any new Brazilian meat plants for export this year because of the coronavirus pandemic, an official at Brazil’s Agriculture Ministry told Reuters, adding that all approvals were on hold until the crisis eases.”