A prolonged military conflict in the Middle East could potentially upend key commodity markets due to Iran’s control of the Strait of Hormuz, one of the world’s most important trade…

COVID-19 Hits Some Domestic Ag Markets, Disrupts Global Supply, As Pres. Trump Highlights Aid to Farmers

Bloomberg’s Mike Dorning reported last week that, “President Donald Trump said he has asked his agriculture secretary to ‘use all of the funds and authorities at his disposal,’ to aid U.S. farmers, whose financial peril has worsened in the coronavirus pandemic.”

....We will always be there for our Great Farmers, Cattlemen, Ranchers, and Producers!

— Donald J. Trump (@realDonaldTrump) April 10, 2020

The Bloomberg article pointed out that, “The administration plans to announce an aid package next week, according to people familiar with the discussions.”

At the direction of @RealDonaldTrump, @USDA is using all financial resources we have been given to develop a program that will include direct payments to farmers & ranchers hurt by COVID-19 & other procurement methods to help solidify the supply chain from producers to consumers. https://t.co/mZocGAfIIk

— Sec. Sonny Perdue (@SecretarySonny) April 10, 2020

Mr. Dorning added that, “[The President’s] tweets did not provide specifics, but the coronavirus relief bill Congress passed last month includes $23.5 billion in aid for farmers. Speaking at a news conference Friday, Trump said his administration will develop a program with at least $16 billion for farmers, ranchers and producers.”

.@USDA will develop a plan to expedite aid to American farmers and keep our supply chain strong. pic.twitter.com/v3h9uNf3lH

— The White House (@WhiteHouse) April 10, 2020

It’s a challenging time in farm country and after securing nearly $25B in resources for our farmers & ranchers in the CARES Act, we’ll continue working w/ @USDA @SecretarySonny to get assistance out quickly and in a way that’s fair. Thank you @POTUS @realDonaldTrump. https://t.co/BiedXzWmeh

— Senator John Hoeven (@SenJohnHoeven) April 10, 2020

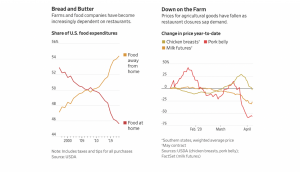

As Corn Belt farmers prepare, and in some instances begin spring planting, Wall Street Journal writers Jesse Newman and Jacob Bunge last week provided a look at how COVID-19 is impacting some domestic agricultural markets.

Newman and Bunge explained that,

Farmers and food companies across the country are throttling back production as the virus creates chaos in the agricultural supply chain, erasing sales to restaurants, hotels and cafeterias despite grocery stores rushing to restock shelves. American producers stuck with vast quantities of food they cannot sell are dumping milk, throwing out chicken-hatching eggs and rendering pork bellies into lard instead of bacon.

The Journal article stated that, “In part, that is because they can’t easily shift products bound for restaurants into the appropriate sizes, packages and labels necessary for sale at supermarkets. Few in the agricultural industry expect grocery store demand to offset the restaurant market’s steep decline.”

“In the dairy industry, restaurant closures and other disruptions have left producers with at least 10% more milk than can be used, according to industry estimates. Dairy groups say the milk glut could grow as supplies increase to a seasonal peak in the spring, and shelter-in-place orders stretch on across the country. In response, cooperatives that sell milk from farmers to processors are asking their members to dump milk, cull their herds or stop milking cows early in an effort to curb production,” the Journal article said.

Last week’s article noted that, “In the poultry market, supermarket shelf-clearing initially juiced prices—lifting boneless, skinless chicken breast prices by 31% over the first three weeks of March, according to data from the U.S. Department of Agriculture. But as restaurant dining rooms sit closed, breast prices dropped by one-fourth in the past two weeks.”

Newman and Bunge added that, “Bacon, more than other pork products, relies on restaurant-industry sales. With pork demand flagging as national chains like McDonald’s Corp. and Denny’s Corp. serve fewer breakfasts, prices for pork bellies have collapsed to a record low. As a result, some major processors are attempting to find other uses for them, such as sausage, or are converting them into lard because it is less costly.”

On Saturday, New York Times writers David Yaffe-Bellany and Michael Corkery reported that, “In Wisconsin and Ohio, farmers are dumping thousands of gallons of fresh milk into lagoons and manure pits. An Idaho farmer has dug huge ditches to bury 1 million pounds of onions. And in South Florida, a region that supplies much of the Eastern half of the United States with produce, tractors are crisscrossing bean and cabbage fields, plowing perfectly ripe vegetables back into the soil.

“After weeks of concern about shortages in grocery stores and mad scrambles to find the last box of pasta or toilet paper roll, many of the nation’s largest farms are struggling with another ghastly effect of the pandemic. They are being forced to destroy tens of millions of pounds of fresh food that they can no longer sell.”

The Times article noted that, “The closing of restaurants, hotels and schools has left some farmers with no buyers for more than half their crops. And even as retailers see spikes in food sales to Americans who are now eating nearly every meal at home, the increases are not enough to absorb all of the perishable food that was planted weeks ago and intended for schools and businesses.

The amount of waste is staggering. The nation’s largest dairy cooperative, Dairy Farmers of America, estimates that farmers are dumping as many as 3.7 million gallons of milk each day. A single chicken processor is smashing 750,000 unhatched eggs every week.

A related news release last week from USDA’s Risk Management Agency (RMA) indicated that, “[RMA] is ensuring that milk producers are not inappropriately penalized if their milk must be dumped because of recent market disruptions caused by the coronavirus pandemic. In addition, RMA is extending inspection deadlines, waiving inspection requirements and authorizing more crop insurance transactions over the phone and electronically to help producers during the crisis.”

The RMA update stated that, “COVID-19 shutdowns have caused disruption in the milk market, and dairy producers are dumping milk as a result. For the 2020 calendar year, RMA is allowing Approved Insurance Providers (AIPs) to count dumped milk toward the milk marketings for the DRP or actual marketings for the LGM-Dairy programs regardless of whether the milk was sold. Producers will still have to provide to the AIPs supporting documentation from the cooperative or milk handler verifying the actual pounds dumped and that the milk was dumped.”

Meanwhile, news reports continue to emphasize logistical obstacles associated with COVID-19 and world-wide food distribution.

Bloomberg writers Jen Skerritt, Leslie Patton, and Emele Onu reported last week that,

The port backups that have paralyzed food shipments around the world for weeks aren’t getting much better. In fact, in some places, they’re getting worse.

“In the Philippines, officials at a port that’s a key entry point for rice said earlier this week the terminal was at risk of shutting as thousands of shipping containers pile up because lockdown measures are making them harder to clear. Meanwhile, curfews in Guatemala and Honduras, known for their specialty coffees, are limiting operating hours at ports and slowing shipments. And in parts of Africa, which is heavily dependent on food imports, there aren’t enough workers showing up to help unload cargoes.

“The port choke-points are just the latest example of how the virus is snarling food production and distribution across the globe. Trucking bottlenecks, sick plant workers, export bans and panic buying have all contributed to why shoppers are seeing empty grocery store shelves, even amid ample supplies.”

The Bloomberg writers explained that, “Food moves from farm to table through a complicated web of interactions. So problems for even just a few ports can ripple through to create troubling slowdowns.”

In other export related news, Reuters Radu Marinas reported last week that, “Romania banned cereal exports to non-European Union destinations during a state of emergency until mid-May, to cover its domestic needs during the new coronavirus outbreak, Interior Minister Marcel Vela said on Thursday.

“Wheat, barley, oat, maize, rice, wheat flour, oilseed and sugar are subject to the military decree issued by the government, Vela told reporters.”

And Reuters writer Maximilian Heath reputed last week that, “Decade-low water levels in Argentina’s Parana River, a key thoroughfare for grains shipments, are forcing exporters to load less merchandise on ships, adding a new problem to a sector already beset by bottlenecks due to the coronavirus pandemic.

“The Parana is Argentina grains superhighway, carrying Pampas grains belt agricultural exports from the Rosario ports hub to the shipping lanes of the South Atlantic. Argentina is the world’s top exporter of soymeal livestock feed and the No. 3 supplier of corn and raw soybeans.

“However, water levels at an 11-year low are limiting the amount of grain ships can take.”