China, the world’s largest soybean importer, has ramped up orders for Brazilian cargoes of the oilseed after meeting an initial shipment volume from the US as part of a trade…

Global Wheat Ending Stocks Tightest Since 2016/17, But Some See Global Food Price Declines for Next Year

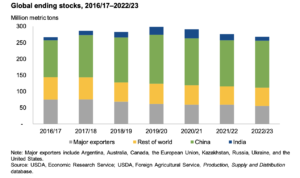

In its monthly Wheat Outlook report earlier this week, the USDA’s Economic Research Service pointed out that, “2022/23 global ending stocks are projected up 0.3 MMT to 267.8 MMT but remain the tightest since 2016/17. China accounts for more than 50 percent of 2022/23 global ending stocks but its stocks are largely not available to the public. When China is removed from the global picture, stocks are even tighter at 123.5 MMT, the lowest since 2007/08. Major exporters’ stocks are forecasted down 0.1 MMT to 55.6 MMT.”

Bloomberg writer Sybilla Gross reported yesterday that, “Strong grain demand will outstrip supply for years to come, stoking more volatility that’s been exacerbated by the war in Europe, according to one of Australia’s biggest wheat exporters.

“With global inventories at historically low levels, pressure on supply is increasing due to the conflict affecting the Black Sea shipping corridor, as well as the lingering effects of the pandemic, said GrainCorp Ltd. Chief Executive Officer Robert Spurway.”

The Bloomberg article noted that, “There’s further demand upside as some importers seek to build buffers, such as increasing inventories, to protect themselves from supply risks, Spurway said. Meanwhile, Ukrainian growers are still facing challenges in getting theirs grains to market, he said.”

Reuters writer Pavel Polityuk reported today that, “Ukraine has exported almost 15.6 million tonnes of grain so far in the 2022/23 season, down 30.8% from the 22.5 million tonnes exported by the same stage of the previous season, agriculture ministry data showed on Wednesday.”

Elsewhere, Bloomberg writers Jonathan Gilbert and Tarso Veloso Ribeiro reported yesterday that, “Just as agriculture traders fix their attention on South America, rain finally fell in Argentina over the weekend and soy farmers started revving up tractors to make up for lost planting time.

“With the soy and corn harvests in the US all but done, the world is now looking to Argentina and Brazil to see if they can produce enough crops to help ease global food inflation.”

“Soy planting in Brazil on Nov. 10 was 69% complete, against 78% last year. In Argentina, it was less than 9% complete versus 17% last year,” the Bloomberg article said.

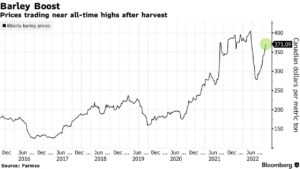

Also yesterday, Bloomberg writers Jen Skerritt and Michael Hirtzer reported that, “Sky-high barley prices are turning Canada’s rare buying-spree of US corn into a habit.

“The price of the grain used to feed cows has soared due to pent-up demand, driving cattle ranchers to turn to US corn as a cheaper substitute to domestic barley. The shift comes one year after a severe drought withered Canadian grain supplies, spurring a switch in trade flows that led the northern neighbor to become one of the biggest buyers of corn from the US Midwest.”

Meanwhile, in a closer look at demand variables in China, Bloomberg News reported yesterday that, “China’s latest efforts to support the economy are lifting the gloom around commodities markets although a sustained recovery in demand is probably still months away.

“Beijing’s twin announcements to deal with its biggest obstacles to growth — a real estate market in crisis and crushing virus controls — have fanned hopes that the government is turning its attention to lifting the economy out of the funk that has persisted for over a year. A thawing in US relations has also lifted sentiment.”

More broadly, Bloomberg writer Alfred Cang reported yesterday that,

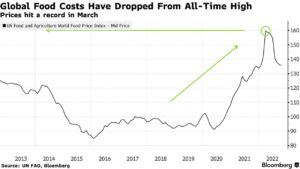

Food prices will probably decline next year, even as global crop stockpiles stay very tight, especially for oilseeds, said David MacLennan, chief executive officer of Cargill Inc., America’s largest private company.

“‘All it takes is one really bad crop, let’s say in North America or South America, to really send prices higher,’ he said at the Bloomberg New Economy Forum in Singapore on Wednesday.

“World food costs jumped to a record in March after the Russian invasion of Ukraine choked off supplies from one of the world’s top exporters. Prices have since declined after a UN-brokered deal to allow ships with Ukrainian grain to pass safely through the Black Sea.”

Bloomberg columnist Javier Blas pointed out yesterday that, “The whole concept of the 2022 food crisis was, from the very beginning, dubious.

“Consider the unequivocal sign of a true crisis: food riots. The world saw them in 2007-2008, when protesters took to the streets in more than 50 nations from Haiti to Bangladesh. But other than in Sri Lanka, a nation blighted by much bigger economic problems, the world didn’t face any significant food riots in 2022. The key savior was the stability of rice, a staple for half of the world’s population. The worst food riots in 2007-2008 weren’t about the price of bread but the cost of a bowl of rice.

“Despite rising corn and wheat costs, rice prices have remained subdued in 2022.”

In other developments, Wall Street Journal writers Laurence Norman, Daniel Michaels and Drew Hinshaw reported today that, “Polish President Andrzej Duda said there was no evidence that a missile that crashed in his country, killing two local workers, was intentional and was likely a Russian-made weapon fired by a Ukrainian air-defense system.

“‘We currently have no evidence that the missile was fired by the Russian side,’ he said. He blamed the tragedy on Moscow’s campaign of missile strikes on Ukrainian targets, including along the Polish border.

“The initial findings were being discussed Wednesday at an emergency meeting at the North Atlantic Treaty Organization, where ambassadors from the alliance’s 30 members and candidates Sweden and Finland reviewed intelligence and considered their options.”