As a result of the attack on Iran, nitrogen fertilizer at the port of New Orleans has seen an increase in price this week. Urea prices for barges in New…

Ag Economy: Farmland Values; and Off-Farm Income

Today’s update looks briefly at recent news items that highlight current information on farmland values. In addition, key parts of a recent Wall Street Journal article that focused on the importance of off-farm income to U.S. farm households are also included.

Farmland Values

In a front page article last week in the Minneapolis Star Tribune, Tom Meersman reported that, “Prices for farmland declined across Minnesota in 2017, another sign of a weak farm economy that’s been plagued by low crop prices and reduced incomes for the past four years.

“Experts say many farmers are dealing with land values about 20 percent lower than when the market peaked in about 2012, when commodity prices were historically high.

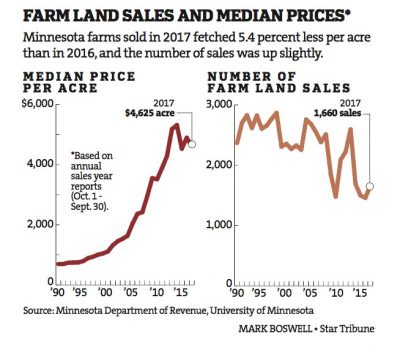

For 2017, numbers based on fiscal year sales data reported to the Minnesota Department of Revenue and analyzed by the University of Minnesota showed that the median price per acre of farmland was $4,625, down 5.4 percent from the previous year.

“‘Land values are an important part of a farmer’s equity, so obviously that land component is an important part of a farmer’s collateral,’ said Bruce Peterson, a former president of the Minnesota Corn Growers Association who farms near Northfield. ‘If that drops 30 percent, then it makes for a much more sticky situation for people in a tighter situation financially.'”

The Star Tribune article noted that, “Last week the Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis reported that the agricultural sector in Minnesota and nearby states remains weak but stable. Lenders responding to a January Fed survey of agricultural credit conditions indicated that farm income and capital spending decreased compared to the previous year, with further declines expected for the coming three months.

“‘We’re in the third to fourth year of farm stress,’ said Ward Nefstead, University of Minnesota Extension economist.”

Last week’s article pointed out that,

‘Land values haven’t gone down as much as they could have,’ said David Bau, a University of Minnesota Extension educator who has been tracking farm economics in southern Minnesota for the past two decades. ‘Prices are starting to hold their own.’

“That’s also true in neighboring states such as Iowa, where a December report from Iowa State University showed average farmland values increasing slightly by 2 percent last year. A January report by Farm Credit Services of Omaha found that South Dakota farmland values dipped by 3.1 percent in 2017.”

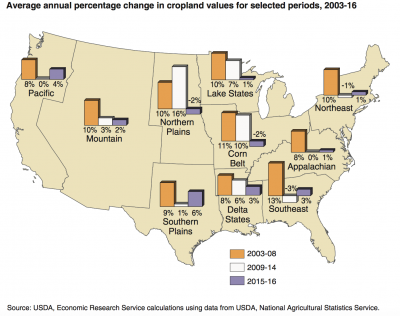

Meanwhile, DTN writer Todd Neeley reported late last week that, “Average Nebraska agriculture land values declined for a fourth-consecutive year, according to preliminary results of a University of Nebraska-Lincoln survey released on Thursday.

“The survey of land professionals that included appraisers, farm and ranch managers and agricultural bankers, points to low commodity prices and state property tax issues as the reasons for the continued fall.

“UNL found average agricultural land values declined by 3% in the past year, and by 17% since reaching an average high of $3,315 per acre in 2014.

The latest survey found Nebraska all-land average values as of Feb. 1 averaged $2,745 per acre.

Preliminary results from the 2018 Nebraska Farm Real Estate Market Survey show a 3% drop in ag land values.https://t.co/yxjnXcB0jk pic.twitter.com/boN9L22bJT

— Nebraska Ag Economics (@UNLAgEcon) March 14, 2018

Off-Farm Income

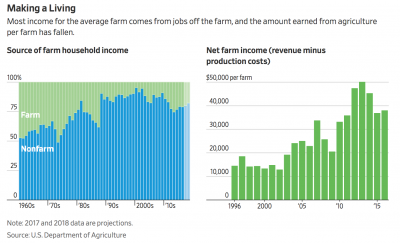

Wall Street Journal writers Jacob Bunge and Jesse Newman reported late last month that, “Most U.S. farm households can’t solely rely on farm income, turning what was once a way of life into a part-time job. On average, 82% of U.S. farm household income is expected to come from off-farm work this year, up from 53% in 1960, according to the U.S. Department of Agriculture.”

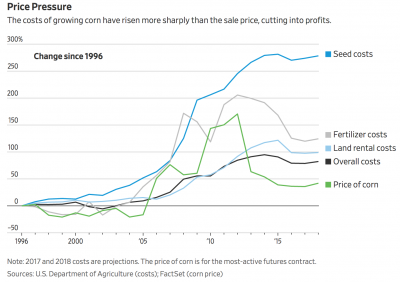

“Off-farm work has become more important since a slump in prices for corn, wheat and other farm commodities over the past five years has cut total U.S. farm income in half. Last week, the USDA said income from farming is expected to fall further over the next decade. Now, picking up work in construction or truck driving is required for many farmers to fund seed and fertilizer purchases, and keep current on loan payments for tractors and land.

‘Most farmers are still on their land today because of their off-farm jobs,’ said Dan Kowalski, head of research at CoBank, one of the largest U.S. agricultural lenders. ‘Without these jobs, these farms would be consolidating at a faster rate.’

The Journal writers explained that, “U.S. food producers as a result are increasingly exposed to economic forces far beyond the fields. Many farms have become reliant not just on sales of crops and livestock, but on the health of rural businesses such as trucking companies and manufacturing plants. Those jobs have been slow to bounce back from the 2008 financial crisis. As of mid-2016, the number of jobs outside of metro areas remained 3% below their prerecession peak, while those in metro areas had grown 5%, according to federal data.

“Rural manufacturers such as Iowa’s Pella Corp. and Hy-Capacity Inc., which rebuilds tractor parts, increasingly support agricultural production by hiring smaller-scale farmers.”

Bunge and Newman pointed out that, “Farmers say their independence and satisfaction from growing a crop keeps them holding down other jobs while working the land. For many farmers who work at Pella, expanding their farms to a size that could provide a complete family income is out of the question. An acre of Iowa’s rich, black soil in the area sells for $4,000 to $8,000, and the state’s average is four times what it was in 2000, according to Iowa State University. Land rental rates in the state have more than doubled in that time.”

The Journal article added that, “Larry Stenger, regional president at First Mid-Illinois Bank & Trust in Sullivan, Ill., said farmers in his region often use their trucking fleets for off-farm work in winter months, transporting grain for nearby elevators or hauling goods for other trucking firms. ‘There are opportunities out there for those looking for it,’ Mr. Stenger said.

“Some larger-scale farmers, who dominate U.S. food production, plow some crop profits into trucking or supply companies to diversify income and insulate themselves from agriculture’s price swings.”