Republicans are debating whether to attach wildfire aid and $15 billion in tariff relief for farmers to a military funding package President Donald Trump is expected to seek for the…

Wall Street Journal- Special Section on Agricultural Issues

Yesterday’s Wall Street Journal included a special section on agricultural issues. The section included several articles that covered a variety of different topics ranging from urban farming, to creative new uses for crops, to export shipping issues. Today’s update highlights articles in yesterday’s paper that focused on farmer’s adaptation to weather changes, the use of big data, and the ultrafiltered milk trade dispute with Canada.

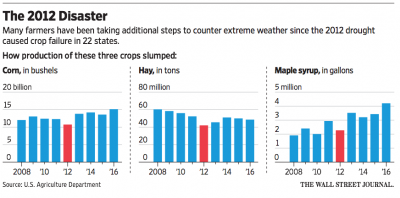

Weather Adaptation Techniques

“More recently, a long dry spell followed by floods in California has hurt farmers there, while throughout the Midwest, Southeast and parts of New England, producers of apples, berries, peaches, maple syrup and other crops have battled dramatic temperature swings.”

Yesterday’s article explained that, “Fred Yoder, a farmer in Plain City, Ohio, says he was lucky to lose just half of his corn, soy and wheat crop in 2012 because he adopted no-till farming, an ancient technique that is being embraced by farmers anew. Instead of removing the remains of previous harvests, the method leaves stalks and roots in the ground to protect the soil from erosion and drought…[N]o-till agriculture is just one of the techniques farmers are adopting to improve the health of their soil. Others are planting cover crops such as legumes and grasses as a way to preserve their soil’s water content in case of a drought.”

Ms. Haddon also pointed out that, “Growers are also trying to plant faster to cut down the growing and harvest season, because the longer the season, the more vulnerable crops are to changing weather. Commercial breeders are working on peppers that could mature before the withering heat of July and August, according to horticulture experts at the University of California, Davis. Some farmers are using GPS systems and satellite-guided planters to seed their fields as quickly and precisely as possible.”

“Other researchers are promoting crops that thrive in more volatile weather and resist pests that become more prevalent as temperatures climb. But it can take decades to develop a new crop variety and bring it to market, and weather patterns are changing much more quickly than that,” the article said.

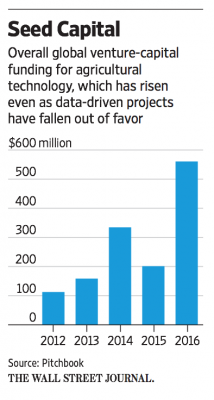

Big Data Use

Eliot Brown reported in yesterday’s Journal that, “For farmers—and the tech companies that want them as customers—data has been a disappointment.

“A few years ago, the agricultural world was full of promises about how the widespread use of data was going to change farming. Companies sprang up that offered to collect huge amounts of information about everything from weather patterns to the soil on farms to the health of crops. The sales pitch: With all this detailed information, farmers would get untold insights into what was happening on their land. And they could use that information to boost production.

But the revolution has been slow to catch on. Many farmers who used the digital services found it difficult to digest the mountains of information and figure out how to put it to use. Many others simply weren’t sold on the idea, or couldn’t afford the investment as crop prices fell.

Mr. Brown indicated that, “This has changed the outlook to the point where venture capitalists, who drove much of the investment into data-based farming, are approaching agriculture in a different way. Instead of betting on legions of companies that provide farmers information, they’re now pumping money into companies that offer tools and services, such as robotic farm equipment, or on biotechnology and genetic editing of plants, that bring faster and more obvious results.”

The article noted that, “In 2016, investments in data-driven agriculture—known as precision agriculture—fell 39% from a year earlier, according to AgFunder, due in part to a broader decline in drone investments. At the same time, investors see promise in agricultural technology that goes beyond data. Venture-capital investments in the agricultural sector overall rose to $560 million last year from $201 million in 2015, according to PitchBook—and that total excludes hardware like satellites that can be used in agriculture but also have other uses.”

The article also stated that, “But even if farmers want information from drones, satellites and on-ground sensors, it is hard to get the most out of them. Many farmers aren’t trained on how to use software to deal with the data and integrate it with their farming equipment, and different types of machines don’t always work together. Spotty or nonexistent cell reception in rural areas makes it hard for machines to communicate.

“Then there is problem of interpretation. While data will tell a farmer things like how much corn a chunk of a field is producing, it is far harder to understand why it is producing and what lessons can be applied to next year’s crop.”

With these issues in mind, the Journal article noted that, “Arama Kukutai, a partner at agtech-focused Finistere Ventures, says that as a result of the integration challenges, his firm is setting its sights on less-crowded agricultural areas.

“Mr. Kukutai’s firm has invested in Plenty United Inc., one of a handful of startups trying to grow leafy greens and other produce in dense indoor locations, through hydroponics and ultraviolet lighting. The theory is that these companies can produce crops like organic lettuce at a level similar to farms, but closer to cities.”

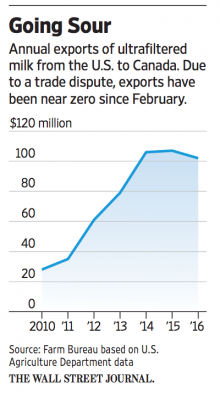

Ultrafiltered Milk to Canada

Matthew Kassel reported yesterday that, “A fight over a little-known dairy product sits at the center of increasing tensions between the U.S. and Canada over broader trade issues.

If the dispute goes unresolved, some observers say, it could have ripple effects in global dairy markets. It also could contribute to efforts by some, including advisers within the Trump administration, to dramatically reshape the North American Free Trade Agreement, which some experts warn could be a disaster for U.S. farmers.

The article provided this background on the issue: “Here’s what is happening. U.S. dairy farmers and processors in Wisconsin, New York and Minnesota have been hurt by a newly adopted Canadian pricing policy that encourages Canadian dairies to buy certain types of milk products domestically. The specific product in the trade dispute is a milk-protein concentrate called ultrafiltered milk that is used primarily in cheese-making to increase yields.

“In 2016, the U.S. exported $102 million in ultrafiltered milk to Canada, according to the U.S. Agriculture Department. But industry observers estimate that exports have dropped to near zero since February, when Canada created a nationwide dairy classification that lowered the price of Canadian milk used to make ultrafiltered milk.”

“Along with timber, the dairy dispute has become a flashpoint in the Trump administration’s tussle with Canada over trade policies,” the article noted.

The Journal article pointed out that, “Attacks by the White House on Nafta are alarming to U.S. agricultural bodies.

“‘If you take Nafta away, all of a sudden it gets more expensive to sell U.S. agriculture products,’ says John Newton, a director of market intelligence at the American Farm Bureau Federation. Nafta has been very good for U.S. farmers, Mr. Newton says, and pulling out could have all kinds of negative effects, such as Mexico shifting corn purchases from the U.S. to South America, or losing an important market for rice.

“For now, the National Milk Producers Federation estimates that U.S. farmers and processors stand to lose about $150 million a year as a result of Canada’s new pricing policy. Jaime Castaneda, senior vice president of the federation, says Canada has the potential to lower global prices for ultrafiltered milk and other milk-protein substances with its new price classification.”

Mr. Kassel added that, “Even though the protein isn’t mentioned in Nafta, its fate is intertwined with that of Nafta because the dispute has forced not just politicians in Washington but also suffering farmers to reconsider the terms—and potential loopholes—of an agreement that was hammered out nearly 25 years ago.”