Bloomberg's Leah Nylen reported Thursday that "a Colorado judge issued an order temporarily blocking the proposed $25 billion merger of Kroger Co. and Albertsons Cos., which has been challenged by…

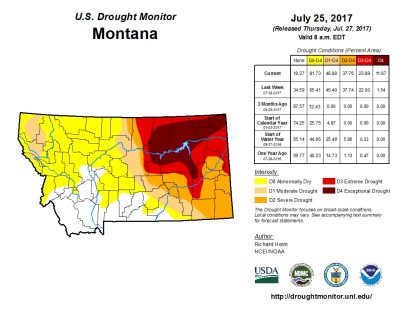

Drought Persists in the Plains

Drought Persists in Plains

Last week, Billings Gazette writer Tom Lutey reported that, “The life had been fading from Grant Zerbe’s stunted chickpeas for the better part of a month, and now drought’s hot breath was burning through the final green inch of every plant stem.

“The Montana farmer’s worst growing season in 30 years was coming to a brutal end. There are few crops to harvest in the region, and with a lack of food and water, unwanted livestock are headed to auction.”

Northeast Montana is experiencing the worst drought in the country.

Mr. Lutey explained that, “Combined with drought in the Dakotas, Montana’s losses contribute to what the U.S. Department of Agriculture expects to be a 64 million bushel loss in wheat production. Durum, a specialty crop for Montana and North Dakota, is expected to be down in bushels 45 percent from last year.”

The Billings Gazette article added that, “Ranchers will lose the most in this drought, said Ed Hinton, an auctioneer who drives down from Scobey for the weekly sale. There’s nothing like crop insurance for livestock. In times of drought, the U.S. Department of Agriculture opens up grasslands previously off limits for conservation. After that, there’s low interest, guaranteed loans.

“But the last thing a rancher needs is to borrow money as his cows head to market earlier and often lighter than expected.”

On Thursday, USDA radio’s Gary Crawford filed a report where he pointed out that, “The Northern Plains drought continues to force cattle producers into making some tough choices.” The one minute audio overview, which included analysis form USDA Livestock, Poultry and Dairy Analyst Shayle Shagam, is available here.

More specifically with respect to spring wheat, Emiko Terazono reported last week at The Financial Times Online that, “As a group of bakers, flour millers and agricultural traders descend on the US northern plains of North Dakota and Minnesota this week, they will be trying to gauge the damage wrought on this year’s crop of top quality wheat by the region’s drought.

“The lack of rain and above normal temperatures have hit the hard red spring wheat, which is used for bread and pasta. Conditions of the crop, known in the industry as the ‘aristocrat of wheat.’ have deteriorated, sending prices soaring to a four-year high.”

The FT article pointed out that, “Weekly crop surveys from the US Department of Agriculture have shown a steady deterioration of conditions for hard red spring wheat, with this year’s harvest forecast at 385m bushels, the lowest since 2002. Inventories, which are supposed to provide a buffer for a drop in output, are forecast at 122m bushels — a 10-year low.”

And earlier this month, Bloomberg writers Sydney Maki and Megan Durisin reported that, “The stunted wheat plants on Robert Ferebee’s parched North Dakota farm were in the worst condition he’d seen in almost three decades. Rather than wait until late July or early August to harvest the crop, Ferebee decided last month to cut his losses and his fields.

A drought across the northern Great Plains has forced growers like Ferebee to conclude that their wheat would be more valuable as cattle feed than baker’s flour.

“They are collecting the crop early — in some cases before grain kernels have fully formed — to avoid further damage, and then bundling the tillers and leaves into hay-like bales rather than sending them through a thresher.”

Approximately 53% of spring wheat production is within an area experiencing drought, @USDA's Weekly Ag in Drought Report pic.twitter.com/eV8TuekG2t

— Farm Policy (@FarmPolicy) July 27, 2017

Beyond the difficulty experienced by ranchers and wheat growers in the northern Plains, Barbara Soderlin reported in Friday’s Omaha World-Herald that, “A deepening drought has become a stressful situation for many Nebraska and western Iowa farmers, made worse by the fact that the price for corn — down by about half since it soared in 2012 and 2013 — isn’t budging.

“‘As you see your yields drop, you want that bigger price to make up for that,’ said [Sioux City-area farmer BJ Hayes], who farms in Nebraska and Iowa. But he’s looking at the one-two punch of less-productive acres and low prices.”

.@OWHnews Nebraska/western Iowa farmers face deepening drought, stagnant prices for their yields https://t.co/LKSrPI9Mmt by @barbarasoderlin pic.twitter.com/p0uAB7MO9z

— Farm Policy (@FarmPolicy) July 28, 2017

The World-Herald article noted that, “The situation wouldn’t be so bad for farmers who are facing big declines in yields — the amount of corn they’ll produce per acre — if they could look forward to a run-up in corn prices to make up lost revenue.

“But only 15 percent of the U.S. corn crop is in drought conditions, the U.S. Department of Agriculture estimated in a Thursday report. The big corn-producing areas of eastern Iowa, Minnesota, Illinois and Indiana are largely untouched by drought.”

Approximately 15% of corn production is within an area experiencing drought, @USDA's Weekly Ag in Drought Report pic.twitter.com/QN3iwcq7mP

— Farm Policy (@FarmPolicy) July 27, 2017

However, Ms. Soderlin added that, “And farmers hit by drought this year won’t make up much ground with insurance payouts because of the way crop insurance programs calculate payments, based on spring market prices, which were under $4 a bushel this year, [Cory Walters, UNL ag economist] said.

Farmers will react by spending less money on equipment purchases and less on family living expenses, Walters said, affecting their local communities. Those are the kinds of decisions that ripple through Nebraska’s wider economy.

Agricultural Economy: Broader Impact

More broadly on the issue of the impact the agricultural economy is having in some states, Brad Davis reported on Thursday at the Omaha World-Herald Online that, “The economies of Nebraska, Iowa and South Dakota logged the worst performance in the U.S. in the first part of the year as a challenged agricultural sector sent growth into negative territory.”

“The data comes from the Bureau of Economic Analysis, a federal agency that is an arm of the U.S. Department of Commerce.”

Agriculture, forestry, fishing, hunting declined 39.8% nationally. This industry subtracted from growth in 39 states https://t.co/eQlmrbUoh5 pic.twitter.com/CmG18H3tIK

— Farm Policy (@FarmPolicy) July 29, 2017

Mr. Davis pointed out that, “Crop prices that remain in the doldrums weigh on the region’s economy, rippling from farms to equipment dealers, merchants, bankers and others — not just in small towns, but into cities, as well.

“Nationally, the Wednesday report showed a category including agriculture declining by 39.8 percent; states whose economies are most tied to ag are suffering the worst, according to the report…”