The frustration in the room at Commodity Classic has been palpable following a year in 2025 where strong production was again unable to overcome swelling costs and expenses. Farmers here…

Crop Choices, Farm Size: Changes in a Time of Low Corn and Soybean Prices

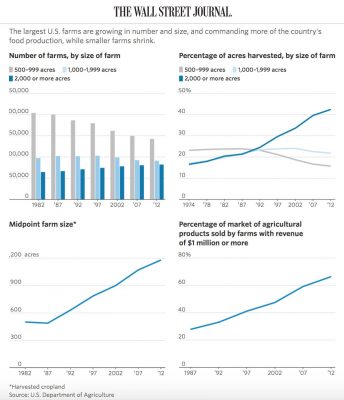

Recent news articles have documented that lower crop prices for commodities such as corn and soybeans have caused some producers to make changes to their traditional crop rotation, or to consider organic crop production methods. More broadly, a recent Wall Street Journal article noted that larger operations may still be able to reap profits in times of lower prices, fueling “a cycle in which size begets size” and where, “smaller-scale farmers struggle to expand their operations to become profitable.”

Background

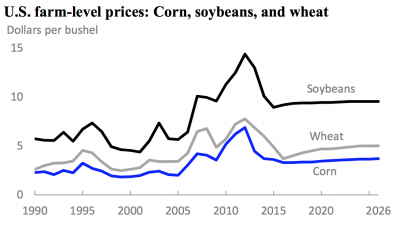

A farmdoc daily update on October 30th stated that, “The monthly average price of corn received by U.S. producers has been less than $3.50 per bushel since August of 2016 and has been below $4.00 for 37 consecutive months.”

And the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s National Agricultural Statistics Service (NASS) indicated in its October Agricultural Prices report that, “The corn price, at $3.27 per bushel, is unchanged from last month but up 5 cents from September 2016.”

The NASS report added that, “The soybean price, at $9.35 per bushel, increased 11 cents from August but decreased 6 cents from September a year earlier.”

Recent news articles have captured examples of how some economic variables are changing in response to these market signals.

Crop Choices: Dry Beans, Organic Crops

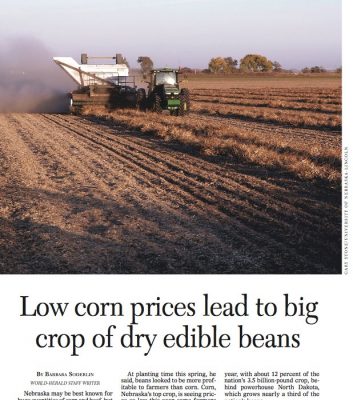

Barbara Soderlin reported late last month in the Omaha World-Herald that, “Nebraska may be best known for huge quantities of corn and beef, but another agricultural commodity is seeing a bumper crop this year: dry edible beans, the kind that go in your chili, burritos and soup.”

The article stated that,

“‘It’s simple economics,’ said bean grower Paul Pieper, who farms in the Panhandle north of Mitchell.

“At planting time this spring, he said, beans looked to be more profitable to farmers than corn. Corn, Nebraska’s top crop, is seeing prices so low this year some farmers are losing money planting it.

“So farmers in areas where beans grow well planted a lot of them — about 40 percent more acres this year than last. And thanks in part to good growing conditions, they expect to see record yields, the U.S. Department of Agriculture said in a report this month.”

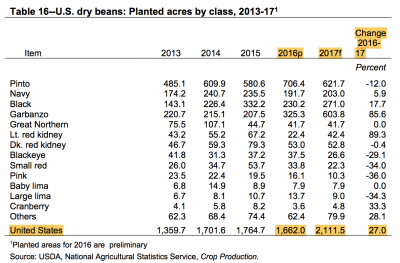

In addition, a report from USDA’s Economic Research Service on October 27th (“Vegetables and Pulses Outlook”) noted that, “A total of 2.033 million acres of dry beans were harvested in 2017, representing an increase of more than 30 percent relative to the 1.558 million acres harvested in 2016. According to the USDA, ERS Farm Sector Income Forecast, returns from growing specialty crops, including pulse crops, were projected to be higher relative to many commodity row crops in 2017.

For example, after experiencing low wheat prices in the 2016/17 marketing year, farmers in traditional spring wheat growing States, including Minnesota, Montana and North Dakota, increased dry bean harvested area by more than 291,000 acres–representing 14 percent of total dry bean area harvested–while spring wheat planted area fell by 400,000 acres. Net farm income from wheat production is estimated at $62,000 (per farm) for 2017, compared to $244,000 per farm for specialty crops.”

Interestingly, the World-Herald article added that, “Now that it’s harvest time, are those farmers seeing the profits they hoped for?

“Prices ran about $28 for 100 pounds at planting time, but since then have fallen to $21 for 100 pounds, said Jessica Groskopf, UNL Extension educator focused on ag economics.

“That’s right around a farmer’s cost to grow beans, she and Pieper said. So farmers generally will see a profit for any crop they sold in advance at planting time, but not much profit for the part of their crop they’d be selling now.

“‘It still looks a little better than corn,’ though, Pieper said.”

Donnelle Eller reported on the front page of the business section in Sunday’s Des Moines Register that,

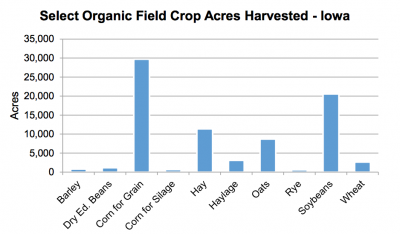

“Although still a small piece of Iowa farming, more and more growers are shifting to organic corn, soybeans and other crops to improve their bottom line.

“The number of Iowa farms and acres certified as organic have each climbed about 5 percent last year over 2015, U.S. Department of Agriculture surveys show.”

The article noted that, “Kathleen Delate, an Iowa State University horticulture professor, said farmers are attracted to organic crops for many reasons, but a leading one is financial.

“‘Organic corn is $8.70 and organic soybeans are $19,’ she said. ‘That’s definitely an enticement in an era of low commodity prices.’

“Conventional corn is selling around $3 a bushel in Iowa, and soybeans are about $9. Both are below the cost to produce the crops, based on statewide averages.”

Ms. Eller pointed out that, “Many Iowa farmers face a fourth year of possible losses.”

Farm Size

A front page article in The Wall Street Journal on October 24th by Jacob Bunge explained that, “Big operations like [Kansas farmer Lon Frahm’s], which he has spent decades building, are prospering despite the deepest farm slump since the 1980s. Years of low prices for corn, wheat and other commodities brought on by a glut of grain world-wide are driving smaller American farmers out of business.

Farms with $1 million or more in annual sales—only 4% of the total—now produce two-thirds of the country’s agricultural output, the largest portion since the U.S. Agriculture Department’s census began tracking the statistic in the ’80s.

The Journal article noted that, “The shift means food production is being increasingly handled by larger farms, which can be more financially secure. It also fuels a cycle in which size begets size, further transforming the rural economy. Smaller-scale farmers struggle to expand their operations to become profitable. Work becomes more scarce. Farm-supply retailers and grain companies are pressured, since larger farms use their size to wrangle better deals.”

The article noted that, “Mr. Frahm estimated that farms of his size can produce $10 million to $15 million worth of grain in a good year. With that amount of production, well-managed farms can reap $1 million to $3 million in profit, even in times of low crop prices, he said.

“A typical smaller farm selling just $500,000 worth of grain annually has over the past three years generated a 5% profit margin, or about $25,000, said Mark Wood, a Colby-based agricultural economist for the Kansas Farm Management Association.”