The U.S. ag economy enters 2026 in a clear crop-sector recession, but the deeper crisis is one of confidence. High input costs, weak prices, policy uncertainty and eroding trust in…

Drought-Tolerant Corn in the U.S., New Report from USDA’s Economic Research Service

Earlier this week, the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s Economic Research Service (ERS) published a report that looked at trends in the development of drought-tolerant corn in the United States. Today’s update looks at some key points from the ERS report.

On Monday, ERS Economists Jonathan McFadden, David Smith, Seth Wechsler, and Steven Wallander published a report titled, “Development, Adoption, and Management of Drought-Tolerant Corn in the United States,” which stated that, “Droughts have been among the most significant causes of crop yield reductions and losses for centuries. Although Federal disaster program and crop insurance payments tend to be higher during droughts, they typically do not fully compensate farmers for drought-related losses.”

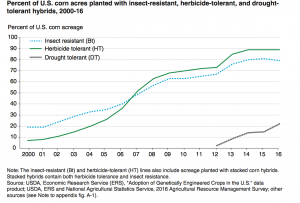

The report explained that, “Drought tolerance in corn is a characteristic that has been the subject of research for decades, but has only recently been commercialized. Drought-tolerant (DT) corn produced using conventional breeding methods was commercially introduced in 2011. Hybrids genetically engineered (GE) for drought tolerance were introduced in 2012, but were not broadly available until 2013. GE drought tolerance protects corn plants from drought somewhat differently than conventionally bred drought tolerance and generally took more time to commercialize, both of which can influence the timing of adoption. However, the vast majority of DT corn planted in 2016 had one or more GE traits (e.g., herbicide tolerance and/or insect resistance).”

The ERS authors pointed out that,

Over one-fifth of U S corn acreage was planted with DT corn in 2016. DT corn accounted for only 2 percent of U.S. planted corn acreage in 2012. By 2016, this share had grown to 22 percent. The pace of adoption is similar to the adoption of herbicide-tolerant corn in the early 2000.

More narrowly, the report pointed out that, “At least 80 percent of DT corn acres were planted in 2016 with seed conventionally bred for drought tolerance. Just under 20 percent of DT corn acres were planted with seed genetically engineered for drought tolerance in 2016. At the national level, 3 percent of all U.S. corn acres in 2016 were planted with seed that had been genetically engineered for drought tolerance.”

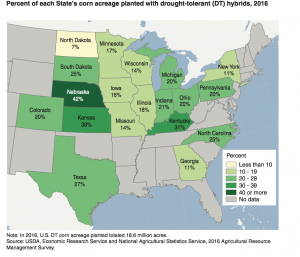

With respect to the geography of DT corn adoption, Monday’s report stated that, “In 2016, drought-tolerant (DT) corn was grown in 18 States where at least 1 million acres of corn were planted. However, adoption rates were highest in areas where DT corn was developed and initially marketed. Over 4 million acres of DT corn—or 42 percent of State corn acreage—were planted in Nebraska, a semi-arid western Corn Belt State. Approximately 2 million acres of DT corn (39 percent of State corn acreage) were cultivated in Kansas, a State with a relatively similar climate. Corn Belt States with relatively wetter climates—Iowa, Illinois, and Indiana—had 1.1 to 2.2 million DT corn acres each, though these acreages represent smaller shares of each State’s total, roughly 16 to 21 percent.”

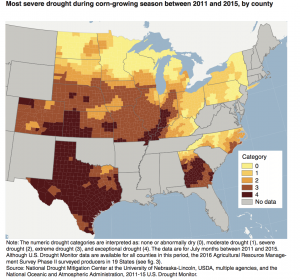

McFadden, Smith, Wechsler and Wallander also indicated that, “Between 2011 and 2015, the most damaging droughts experienced during the corn-growing season in each county of our 19-State survey area tended to be classified as severe, extreme, or exceptional. The most severe drought for many counties during this period occurred in 2012 and was particularly serious in Colorado, western Texas and Kansas, southern Missouri and Illinois, western Kentucky, and certain areas of Indiana and Georgia.”

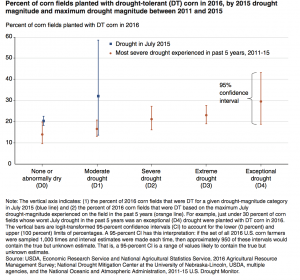

Following this point, the ERS report noted that, “Regional differences in drought severity and recentness of exposure significantly influence adoption of DT corn.

Only 14 percent of fields located in areas that did not experience a July drought (i.e., none or abnormally dry classifications) from 2011 to 2015 were planted with DT corn in 2016. By contrast, 30 percent of corn fields located in areas where the most severe July drought was ‘exceptional’ (i.e., D4 classification) at some point between 2011 and 2015 were planted with DT hybrids in 2016.

After discussing a variety of other variables in more depth, the ERS report concluded by stating that, “By 2016, approximately 22 percent of national corn acreage consisted of drought-tolerant (DT) corn hybrids. Diffusion of this new technology has been partially driven by farmers’ experiences with drought: adoption is highest in semi-arid regions of the western Corn Belt where these seeds were partly developed and where companies’ marketing efforts were initially concentrated. The expected benefit from DT corn adoption is likely to be higher in dry or drought-prone corn-producing regions than in regions with ample rainfall.”

The authors added: “The decision to plant DT corn can be likened to farmers’ decisions to purchase insurance. Under mild-to-moderate drought conditions, planting DT corn can ‘pay out‘ in the form of reductions in drought-induced yield losses. Farmers who adopt DT corn value the expected avoidance of such yield losses at least as much as the premiums they are willing to pay for the DT technology.

However, DT seeds provide incomplete protection from drought, and substantial losses could result under severe conditions. Under extreme or exceptional drought, there could be little expected benefit to adoption since both DT and non-DT corn are likely to suffer crop failure.

“Yet, there remain conditions under which DT corn may be an effective risk-management tool.

“Broad policy implications stem from these potential improvements in risk management. Under mild-to-moderate drought conditions, the decision to plant a DT corn hybrid could determine whether a farmer suffers losses that warrant filing a Federal crop insurance claim. Continued diffusion of DT corn and further development of drought tolerance in other field crops could result in cost savings to farmers, private insurers, and the Federal Government through reduced indemnity payments. Similar reductions in drought-related natural disaster payments could also occur under increasing adoption and technological improvements.”