Bloomberg's Leah Nylen reported Thursday that "a Colorado judge issued an order temporarily blocking the proposed $25 billion merger of Kroger Co. and Albertsons Cos., which has been challenged by…

Some Kinks in Food Supply Chain Persist During COVID-19 Fallout

Bloomberg writer Michael Hirtzer reported late last week that, “American beef output is down a lot more than plant closures would have you believe — a sign that slowdowns at facilities will continue to keep meat supplies tight even when some production lines reopen.

Cattle slaughter dropped 37% this week from a year ago, U.S. Department of Agriculture data show. That far outstrips the 10% to 15% in capacity that’s been halted with meat plants closed after coronavirus outbreaks among employees. Hog slaughter was down 35%, also topping the shutdown figure of 25% to 30%.

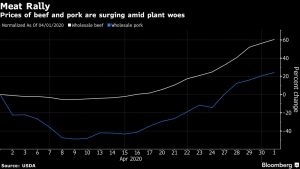

The Bloomberg article pointed out that, “Already, some grocers are beginning to ration supplies as the virus forces unprecedented disruptions in meat processing. Kroger Co., the nation’s biggest traditional supermarket chain, on Friday said it was limiting purchases of ground beef and fresh pork ‘at select stores.’ Wholesale prices for both the meats have surged, and it’s starting to translate into higher bills at the retail level.”

On Monday, Washington Post writer Laura Reiley reported that, “President Trump’s executive order last week requiring meat processing plants to stay open to ward off shortages may not be a cure-all for the food industry segment that has been hardest hit by coronavirus outbreaks.

“The company has been severely affected. Three of Tyson’s six main U.S. processing facilities remain closed, and three others are operating at reduced capacity, the company said.”

1/ Weekly #Livestock, #Poultry & #Grain Market Highlights May 04, https://t.co/AmqkAC8Kql… @USDA_AMS

— Farm Policy (@FarmPolicy) May 4, 2020

* #Pork production, down ~35% from last year.

* #Beef production, down ~35% from last year. pic.twitter.com/hTdvqolRsx

The Post article noted that, “Steve Meyer, an economist for Kerns and Associates, an agricultural risk management firm, said Tyson’s production numbers may be even more dire.

‘By my calculations, last Friday, pork production was down 42.9 percent for all U.S. companies,’ he said by phone Monday. ‘Tyson, by my calculations, was down by 57,780 hogs processed per day from a capacity of 78,500 processed per day. That’s 74 percent short.’

Reuters writers Tom Polansek and Uday Sampath Kumar reported on Monday that, “The coronavirus crisis will continue to idle U.S. meat plants and slow production, Tyson Foods Inc said on Monday, signaling more disruptions to the U.S. food supply after U.S. President Donald Trump ordered facilities to stay open.”

“The country’s capacity to slaughter hogs has dropped by about 50% from before the pandemic, Tyson President Dean Banks told analysts. The company consolidated its product offerings to help keep supplies flowing to consumers, he added later on a call with reporters,” the Reuters article said.

And Jacob Bunge reported on Monday at The Wall Street Journal Online that, “Covid-19 outbreaks among workers at meatpacking plants have forced closures at Tyson and other companies like Cargill Inc., JBS USA Holdings Inc. and Smithfield Foods Inc. Other plants remain open but with curtailed operations as health worries keep many workers home. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention last week estimated 4,913 coronavirus cases among workers at 115 U.S. meat plants, and 20 deaths.”

Mr. Bunge added that, “Plant closures and slowdowns have cut into overall meat production, leading some supermarket operators to brace for shortages. Tyson is dealing with shortfalls in some products for both grocery stores and restaurant customers, executives said, and the company is focusing its capacity on products that can be made the fastest and in the highest volumes.”

Union president reacts strongly to the White House executive order to reopen meat plants: Trump administration is taking the wrong approach...need to make people feel safe...our members are getting sick and dying.https://t.co/9v9IscqY67 pic.twitter.com/0jocAo73oW

— Bloomberg TV (@BloombergTV) May 4, 2020

Brett Molina reported in Monday’s USA Today that, “Concerns about a potential meat shortage bubbled in recent weeks following comments from Tyson Foods Chairman John Tyson warning of a ‘vulnerable’ supply chain caused by meat processing plants shutting down due to coronavirus outbreaks.”

The article noted that, “‘What the plant closures create is somewhat of an hourglass effect with plenty of supply in the bottom part and plenty of demand in the top part with the reduced processing capacity creating a bottleneck,’ said Olga Isengildina-Massa, Associate Professor at the Department of Agriculture and Applied Economics for Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University.”

And late last week, Associated Press writer Stephen Groves reported that, “Signs Friday that several big meatpacking plants will soon reopen might appear to support President Donald Trump’s assertion that he had ‘solved their problems’ in keeping grocery stores’ coolers stocked during the coronavirus crisis. But the reality isn’t likely to be so easy.

“Though meatpackers have been moving to shift operations to make employees less vulnerable to coronavirus infection, they still have a workforce depleted by illness, with at least 4,900 employees nationwide infected. Many others may be unwilling to risk entering plants that have been rife with infections. Even plants that keep the production lines moving will have to do so more slowly, renewing concerns about whether Americans can count on seeing as much meat as they’re used to.”

All parts of Iowa’s ag economy are feeling the devastating effects of the #coronavirus pandemic and farmers are struggling due to an uncertain future.

— Sen. Grassley Press (@GrassleyPress) May 4, 2020

Listen to the stories of Iowa farmers featured this weekend on @NewsHour: pic.twitter.com/p8rGqZ7jFl

Also last week, Associated Press writer David Pitt reported that, “After spending two decades raising pigs to send to slaughterhouses, Dean Meyer now faces the mentally draining, physically difficult task of killing them even before they leave his northwest Iowa farm.

“Meyer said he and other farmers across the Midwest have been devastated by the prospect of euthanizing hundreds of thousands of hogs after the temporary closure of giant pork production plants due to the coronavirus.

“The unprecedented dilemma for the U.S. pork industry has forced farmers to figure out how to kill healthy hogs and dispose of carcasses weighing up to 300 pounds (136 kilograms) in landfills, or by composting them on farms for fertilizer.”

The AP article added that, “Officials estimate that about 700,000 pigs across the nation can’t be processed each week and must be euthanized. Most of the hogs are being killed at farms, but up to 13,000 a day also may be euthanized at the JBS pork plant in Worthington, Minnesota.”

"I think the food system is under strain but it is incredibly resilient," says Cargill CEO David MacLennan on the impact of #COVID19 on food supply chains. pic.twitter.com/scNLDqFM8N

— Squawk Box (@SquawkCNBC) May 1, 2020

In other COVID-19 supply chain impacts, Jeanette Marantos reported on the front page of Monday’s Los Angeles Times that, “The coronavirus pandemic has left Washington’s farmers with at least a billion pounds of potatoes they can’t sell, a new crop growing without any buyers and millions of dollars in debt they have no way to pay.”

The article stated that, “Normally, [farmer Marvin Wollman’s] storage sheds would be nearly empty this time of year, but more than half his potatoes — ‘Let’s just say millions of pounds‘ — are still piled high in the cavernous buildings, which are roughly the size of a football field with roofs nearly 30 feet high.”

“‘We’re afraid there’s still going to be potatoes in storage when we go to dig up this year’s crop in September,’ Wollman said. ‘These are good potatoes. We don’t want to throw them away. It’s just, what do you do with them?’

“As it turns out, getting rid of a billion pounds of spuds isn’t easy — or cheap. It usually takes Washington farmers a year to sell that quantity to grocery stores.”

The LA Times article added that, “Congress recently approved $9.5 billion for the Coronavirus Food Assistance Program to help farmers with crops they can’t sell. The maximum relief for single-commodity farmers is $125,000, but most borrow millions each year to cover their costs until their crop can be sold.

‘It’s like you’re drowning in nine feet of water, and we take an inch away,’ said Rep. Kim Schrier, a freshman Washington Democrat on the House Agriculture Committee. ‘You’re still drowning.’

“Washington potato farmers hope the U.S. Department of Agriculture will step in and buy their billion-pound glut, then donate the potatoes to food banks or even cattle ranchers as supplemental livestock feed.”