The world's farmers face soaring fertilizer and fuel prices as the war in the Middle East escalates, leaving some scrambling for supplies as the spring planting season approaches and causing…

A Quarter of Sunflower Oil Has “Vanished” – Brazil Eyes “Tropical Wheat,” and Fertilizer Problems Persist

Christine Hauser reported in today’s New York Times that, “First the coronavirus, then the war. Just as the pandemic caused shortages of essential items, Russia’s invasion of Ukraine has disrupted important food supplies, driving up prices of staples like cooking oil in supermarkets around the world.

“Before the war, Ukraine was the world’s largest exporter of sunflower oil. The conflict has now paralyzed harvests and left many nations with limited stocks of edible oil and soaring prices for what’s left — worsening a food crisis in East Africa and leading to export restrictions in Indonesia. Some shoppers, most recently in Britain, are being limited in their purchases of cooking oils, as supermarkets and restaurants adjust to the climbing costs.”

Hauser explained that, “Supermarket chains in Spain, Greece, Turkey, Belgium and other nations have limited cooking oil purchases, sometimes describing the moves as precautions in the face of increased demand, according to local news outlets. At Tescos, a major British chain, customers can buy up to three bottles of edible oil, ‘so that everyone can get what they need,’ as a flyer posted on a shelf says.”

“The disruption was so jarring that Britain’s food standards agencies said last month that manufacturers were replacing cooking oils with rapeseed oil so ‘urgently’ that some had been unable to change their labels as quickly,” the Times article said.

Today’s article added that, “[Kate Halliwell, the chief scientific officer of the Food and Drink Federation, which represents Britain’s largest manufacturing sector] said a quarter of the sunflower oil on the global market has ‘vanished‘ in the wake of the sanctions imposed on Russia, which cut off its industries from many markets. Adding to the uncertainty is how much sunflower seed was planted in Ukraine and how much harvest can make it to markets, she said.”

Meanwhile, Reuters writer Pavel Polityuk reported today that, “Ukraine could lose tens of millions of tonnes of grain due to Russia’s blockade of its Black Sea ports, triggering a food crisis that will affect Europe, Asia and Africa, President Volodymyr Zelenskiy said on Monday.

“‘Russia does not let ships come in or go out, it is controlling the Black Sea,’ Zelenskiy told the Australian news programme 60 Minutes. ‘Russia wants to completely block our country’s economy.'”

And Wall Street Journal writer Samantha Pearson reported late last week that, “Deep in the sweltering savanna of central Brazil, a quiet farming revolution is under way, promising relief as Russia’s war in Ukraine sparks food shortages.

Here in the tropics, growing wheat—a crop best suited to mild temperatures—was once considered a crazy idea. Now, new varieties of protein-rich ‘tropical wheat’ created by state agronomists are already starting to reap record harvests and profits.

“With higher prices attracting farmers, analysts are predicting as much as a 40% increase in national wheat production to almost 11 million tons this year.”

The Journal article noted that, “‘Brazil has everything it needs to become one of the world’s biggest producers,’ said Celso Moretti, an agronomist and head of Embrapa, Brazil’s agricultural research agency. Currently a net importer of wheat, Brazil has the capacity today to triple wheat production to 22 million tons on existing farmland in the next few years, turning the country into one of the world’s 10 largest exporters, he said.

“While the effort to grow these new varieties started before the invasion of Ukraine in late February, the timing couldn’t be better. With almost 50 countries dependent on Russia and Ukraine for at least 30% of their wheat imports, the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations warns disruptions caused by the war could lead to widespread hunger in the poorest nations.”

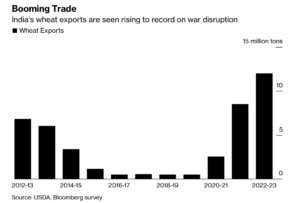

Also with respect to wheat production, Bloomberg’s Pratik Parija reported yesterday that, “A blistering heat wave has scorched wheat fields in India, reducing yields in the second-biggest grower and damping expectations for exports that the world is relying on to alleviate a global shortage.

“Temperatures soared in March to the highest ever for the month on record going back to 1901, shriveling India’s wheat crop during a crucial growth period. That’s spurring estimates that yields have slumped 10% to 50% this season, according to almost two dozen farmers and local government officials surveyed by Bloomberg.”

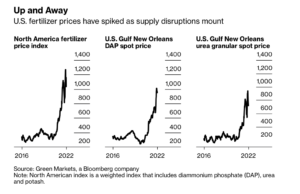

And in other developments regarding the ongoing market adjustments to higher fertilizer prices, Bloomberg writers Elizabeth Elkin and Samuel Gebre reported this week that, “For the first time ever, farmers the world over — all at the same time — are testing the limits of how little chemical fertilizer they can apply without devastating their yields come harvest time. Early predictions are bleak.

“In Brazil, the world’s biggest soybean producer, a 20% cut in potash use could bring a 14% drop in yields, according to industry consultancy MB Agro. In Costa Rica, a coffee cooperative representing 1,200 small producers sees output falling as much as 15% next year if the farmers miss even one-third of normal application. In West Africa, falling fertilizer use will shrink this year’s rice and corn harvest by a third, according to the International Fertilizer Development Center, a food security non-profit group.”

The Bloomberg article stated that, “For the billions of people around the world who don’t work in agriculture, the global shortage of affordable fertilizer likely reads like a distant problem. In truth, it will leave no household unscathed. In even the least-disruptive scenario, soaring prices for synthetic nutrients will result in lower crop yields and higher grocery-store prices for everything from milk to beef to packaged foods for months or even years to come across the developed world. And in developing economies already facing high levels of food insecurity? Lower fertilizer use risks engendering malnutrition, political unrest and, ultimately, the otherwise avoidable loss of human life.”