Bloomberg's Leah Nylen reported Thursday that "a Colorado judge issued an order temporarily blocking the proposed $25 billion merger of Kroger Co. and Albertsons Cos., which has been challenged by…

Iowa Farmers Dealing With Late Planting, Higher Input Costs, While Elevated Food Costs Put Focus on China

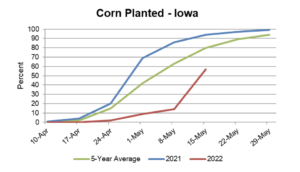

Donnelle Eller reported on the front page of today’s Des Moines Register that, “This year’s planting season is about as unusual as Blake Reynolds can recall: Snow, rain and cold meant he started planting corn and soybeans this year in mid-May, about when he finished planting his crop last year. And the year before.

“‘We’ve been spoiled with good planting conditions the past couple years,’ said Reynolds, who farms several thousand acres near Indianola.

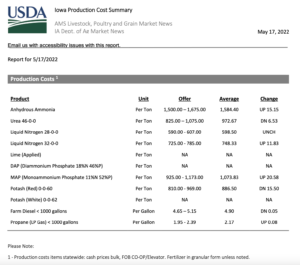

“The late start isn’t the only challenge. While Iowa farmers have waited to get into the fields, corn and soybean prices have climbed near record highs — but so, too, have the cost of the seed, fertilizer and chemicals farmers need to grow crops.

That’s if they can get them at all. A third of the farmers in a Purdue University survey said they have had difficulty buying inputs: 30% struggled to get herbicides; 27%, farm machinery parts; 26%, fertilizers; and 17%, insecticides.

Today’s article noted that, “‘Going back to the 1970s, there’s only been a couple of times when producers had any kind of input availability issues,’ said James Mintert, a Purdue agricultural economist who leads the Purdue/CME Group Ag Economy Barometer, a monthly survey weighing farmer sentiment.”

Eller explained that, “Among the chief complications: The global pandemic continues to cause supply chain disruptions, experts say, especially impacting Chinese-manufactured chemicals coming to the U.S. Also, the world fertilizer supply has shrunk after Russia, the source of about 20%, came under trade sanctions following its invasion of Ukraine.”

“It’s not that farmers aren’t able to find fertilizer or herbicide, Mintert said. They just may not find the products they wanted. ‘Farmers need to have a Plan A, B and C,’ Mintert said.”

The Register article pointed out that, “Despite the rising costs, many farmers likely will be able to turn a profit this year, with rising corn, soybean and other commodity prices offsetting expenses, Mintert and others said. But locking in profits next year will be much more difficult, with farmers bearing the full brunt of price increases and uncertainty about where commodity prices will land if Ukraine and Russia, both major corn growers, end the fighting that is disrupting their production.”

Today’s article added that, “Among farmers surveyed for Purdue’s Ag Economy Barometer, 60% expect expenses to climb by nearly a third over the next 12 months. ‘They’re worried about a potential cost-price squeeze,’ Mintert said.”

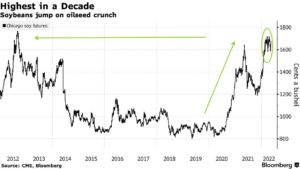

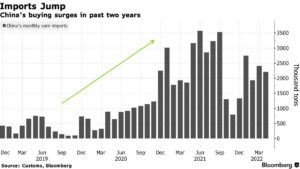

Meanwhile, Bloomberg writer Jasmine Ng reported yesterday that, “[China] still buys about 60% of all the soybeans that are traded internationally, and ranks as the biggest corn and barley importer. It has also recently emerged as one of the world’s largest wheat buyers. That makes soaring global crop costs and, potentially, a looming world food crisis very much a matter of concern for the government, especially in terms of how local prices perform.”

The Bloomberg article noted that, “China’s local consumption of soybeans is almost as large as the entire US harvest, and the country has to import about 85% of its needs. The beans are crushed into edible oil for cooking and other food uses, and into feed for its hog population, the world’s largest. Global soybean prices have doubled in the past two years on dry weather in South America and a shortage of oil-bearing seeds. Unless the US has a bumper crop this year, they could go even higher.”

“The government is making a big push to boost soybean production, with the crop poised to jump 19% in 2022-23. But with output so low compared with consumption, that isn’t going to make much of an impression on imports.”

Yesterday’s article stated that, “Unlike soybeans, however, where the country has been highly dependent on foreign supplies, corn imports only accounted for about 10% of domestic consumption in the 2020-21 year, and that percentage is on track to shrink to about 6% by 2022-23, according to data from the US Department of Agriculture.”

The Bloomberg article indicated that, “The world’s supply of wheat is under threat as everything from war to drought, floods and heat waves cut production. Global wheat prices soared to a record in March after Russia invaded Ukraine, and they are 80% more expensive than they were a year earlier, helping push global food costs to the highest ever.

“Like corn, the country’s dependence on imports is low at about 7% of consumption in 2021-22. That still makes it one of the world’s top buyers along with Indonesia, Egypt and Turkey.”

Looking ahead, the Bloomberg article pointed out that, “China has built up huge stockpiles of wheat, rice and corn, and according to USDA estimates, the country holds at least half, if not more, of global inventories for these commodities. The government will release stockpiles if needed to alleviate any food inflation or shortages, said Iris Pang, chief economist for Greater China at ING Bank. Fertilizer costs are a concern and could push up food inflation, but ‘not to a worrying situation,’ she added.

“Over the longer term, Beijing has called for stronger measures to stabilize production, with two priorities: new seeds and protection of arable land. It’s seeking to develop genetically modified seeds to boost yields, and wants to stop farmland being used for construction or turned into golf courses.”