As a result of the attack on Iran, nitrogen fertilizer at the port of New Orleans has seen an increase in price this week. Urea prices for barges in New…

Amid Production Concerns, Food Import Costs Heading For Record, While Export Ban Worries Persist

Yusuf Khan reported in today’s Wall Street Journal that, “The European Union faces a disappointing wheat harvest this year, dimming hopes that one of the world’s biggest producers might help fill a widening global grain gap left by the war in Ukraine.”

“Amid the tight global market, though, any expected shortfall from a big grain producer has become a source of fresh worry. In recent weeks, the EU’s harvest—one of the world’s largest—has become a particular key focus for grain buyers and agricultural analysts as they debate whether it might disappoint, and so add to the current deficit,” the Journal article said.

Khan noted that, “Strategie Grains, an agriculture consulting firm that publishes a closely followed monthly crops report, said Thursday it is now forecasting the EU to produce almost 5% less wheat this year compared with last year. The bloc is forecast to produce 278.8 million metric tons of all grains in the 2022-2023 growing season—down more than 4% from last year—because of dry weather. Coceral, a European trade association, earlier forecast grain production across the EU to fall 1.4% from 2021.”

The Journal article added that, “The U.N. FAO said Thursday in its twice-a-year Global Food Report that global grain production—which includes crops such as corn, wheat and other grains—is expected to hit 2.78 billion metric tons in 2022, down 16 million metric tons from 2021. While a relatively small decrease, it is the first decline in four years, the U.N. said.”

In other production related news, Reuters writer Maximilian Heath reported yesterday that, “Argentina’s 2022/23 wheat crop will likely come in at 18.5 million tonnes, down from 19 million tonnes previously estimated, the Rosario grains exchange said early on Thursday, citing reduced planting by farmers due to dry weather.”

And earlier this week, Bloomberg News reported that, “Chinese President Xi Jinping reviewed efforts to boost domestic grain production in Sichuan province, as Russia’s war in Ukraine continues to destabilize global food security.”

“China is one of the world’s biggest wheat importers, leaving it particularly exposed to the effects of President Vladimir Putin’s invasion of Ukraine, a major shipper of grains such barley, corn and wheat. That’s prompted the Asian nation’s state stockpiling company to buy newly harvested wheat for national reserves at record prices this month,” the Bloomberg article said.

Amid global production concerns, food import prices are rising, and have sparked worry about export restrictions.

Associated Press writer Frances D’Emilio reported yesterday that,

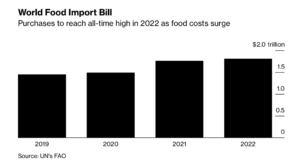

Food import bills will reach a record high this year and food markets are likely to tighten around the world, according to a glum new forecast by a U.N. food agency.

“The Food Outlook, issued twice a year by the Food and Agriculture Organization, also found that ‘many vulnerable countries are paying more but receiving less food‘ in imports.”

“The forecast cited ‘soaring input prices, concerns about the weather, and increased market uncertainties stemming from the war in Ukraine,’ which has seen millions of tons of grain stuck in silos and unable to be shipped abroad from that major agricultural exporter due to the Russian invasion,” the AP article said.

And Bloomberg writer Megan Durisin reported yesterday that, “The global food import bill is set to reach a fresh record in 2022, but surging prices mean buyers will barely be getting any more for the money.”

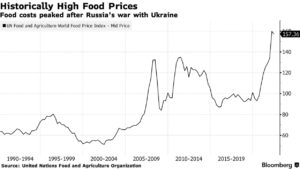

Durisin pointed out that, “An FAO index of food prices surged to a record earlier this year as Russia’s invasion of Ukraine curtails shipments from one of the world’s biggest suppliers of vegetable oils and grains. Soaring energy and fertilizer prices are also making it increasingly expensive to produce crops and livestock.

“That’s raised concerns about global hunger, and the report shows the spike in food costs is already taking a toll on vulnerable areas.”

In a closer look at export policy issues, Bloomberg’s Bryce Baschuk reported yesterday that, “A plan proposed by the Group of Seven nations to mitigate a looming global food crisis is confronting an immovable force — India.

“Next week in Geneva, the world’s trade ministers will consider a proposal that’s backed by more than 50 nations to avoid a cascade of international food export restrictions that may spark destabilizing, hunger-driven conflicts in the world’s most volatile regions.

“But Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s decision to ban wheat exports from India is thwarting international efforts to combat rising food prices.”

The Bloomberg article noted that, “Faced with the prospect of rising food prices at home, more than two dozen nations have responded with export restrictions for food and fertilizer, according to data provided by the University of St. Gallen’s Global Trade Alert.

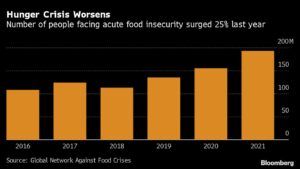

“At a time when nearly 200 million people are already facing crisis-level food insecurity, there’s a risk that this trend toward protectionism could lead to a domino effect and aggravate shortages in net food importing nations like Egypt.”

And New York Times writer Mike Ives reported today that, “As Russia’s invasion of Ukraine helped push global agricultural prices to soaring heights, some Asian governments restricted the export of products they viewed as essential to domestic food security.

For Indonesia it was cooking oil. For India, wheat. And for Malaysia, chickens.

“But the bans risk hurting farmers and producers, and one concern is that the current cycle of protectionism could lead to restrictions on other food exports — including rice, a primary food for more than half the world’s population. That concern was amplified last month, when an official from Thailand said the country was considering setting up a rice price pact with Vietnam, another major rice exporter, to help the two nations boost their ‘bargaining power.'”

Ives explained that, “Now a primary concern is that the region’s food export restrictions will multiply and spill over into other commodities, including rice, the food stock of the world’s poor. Some say the current situation carries echoes of 2008, a year when some of the world’s largest rice exporters, including India and Vietnam, restricted their exports, sending consumers panicking and prices soaring.”