The frustration in the room at Commodity Classic has been palpable following a year in 2025 where strong production was again unable to overcome swelling costs and expenses. Farmers here…

Ogallala Aquifer Depletion Threatening Rural Communities & Ag

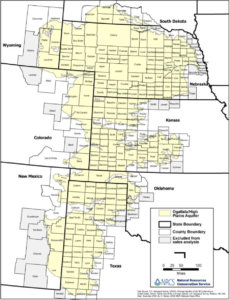

The Kansas Reflector’s Allison Kite and Kevin Hardy reported Monday that “disappearing water” in the Ogallala Aquifer, which stretches from South Dakota to Texas, “is threatening more than just agriculture. Rural communities are facing dire futures where water is no longer a certainty. Across the Ogallala, small towns and cities built around agriculture are facing a twisted threat: The very industry that made their communities might just eradicate them.”

“Kansas Democratic Gov. Laura Kelly acknowledges some communities are just a generation away from running out of water,” Kite and Hardy reported. “But she said there’s still time to act. ‘If they do nothing, I think they’re going to suffer the consequences,’ Kelly said in an interview.”

Why the Aquifer is Important

The Ogallala Aquifer is one of the most crucial water sources in the United States for both agricultural production and for daily water use in households. According to Oklahoma State University, “approximately 14 percent of the total aquifer area consists of irrigated acres capable of producing $7 billion in crop sales. The Ogallala aquifer provides one-fourth of the total water supply used for agricultural production across the U.S.”

Kite and Hardy report that that adds up to “20% of the nation’s wheat, corn, cotton and cattle production and represents 30% of all water used for irrigation in the United States.”

“The water from the aquifer is being pumped by nearly 200,000 irrigation wells, most of them installed since the 1940s,” according to the Encyclopedia of the Great Plains. “Installation rates have varied, with the highest rates generally occurring during dry years.”

Aquifer Concerns

Concerns about the water level of the Ogallala Aquifer are nothing new. Scientific American’s Jane Braxton Little reported on the need to save the water in the aquifer in March 2009.

“The Ogallala Aquifer, the vast underground reservoir that gives life to these fields, is disappearing. In some places, the groundwater is already gone,” Braxton Little wrote. “This is the breadbasket of America — the region that supplies at least one fifth of the total annual U.S. agricultural harvest. If the aquifer goes dry, more than $20 billion worth of food and fiber will vanish from the world’s markets.”

Concerns about water depletion have continued in recent years, with the Texas Tribune’s Jayme Lozano Carver reporting in 2023 that “water levels in the Ogallala Aquifer, also known as the High Plains Aquifer, have dropped consistently in the region over the last five years.”

“Since the mid-20th century, when large-scale irrigation began, water levels in the stretches of the Ogallala underlying Kansas have dropped an average 28.2 feet farther below the surface, far worse than the eight-state average of 16.8 feet,” Kite and Hardy wrote. “Water levels in Texas, where the Ogallala runs under the state’s panhandle, have dropped 44 feet. New Mexico has seen a 19.1-foot decline. In Colorado, Nebraska, Oklahoma and Wyoming, the water level has declined less than the eight-state average, while in South Dakota it has risen.”

Community Concerns

“Communities will still need to get more aggressive about conserving water, said Michael Morris, who leads the water authority board and is mayor of Clovis (New Mexico), one of its member communities,” according to Kite and Hardy. “Morris is active in agricultural efforts to decrease pumping — such as conservation programs in the region that pay producers to stop pumping. And the city is working to expand water recycling efforts. But he said the situation is even more dire than locals realize.”

“Without drastic measures, some communities may not survive,” Kite and Hardy wrote. “‘I think, without a doubt, we will see some communities dry up,” (Peter) Gleick said in an interview. ‘We’ve seen that historically, where communities outgrow a natural resource or lose a natural resource and people have to move to abandon their homes.'”