A bipartisan group of former leaders of America's major agricultural commodity associations and biofuels organizations, farmer leaders, and former senior USDA officials sent congressional ag leaders a letter on Tuesday…

Farm Income to Fall in 2026 Despite Hefty Gov’t Payments

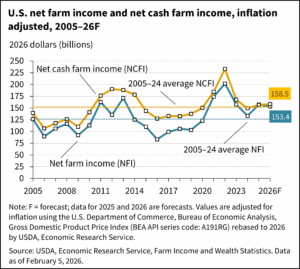

Reuters’ P.J. Huffstutter reported that “in a sign of growing stress for U.S. farmers, the Agriculture Department forecast on Thursday that U.S. net farm income would fall 0.7% this year, despite near-record government payments that are expected to account for nearly 29% of producers’ bottom line.”

“Net farm income, a broad measure of profitability in the agricultural economy, is forecast to drop 0.7% to $153.4 billion in 2026 from the year before, USDA said,” Huffstutter reported. “When adjusted for inflation, net farm income is projected to decrease by $4.1 billion or 2.6%.”

“Without government payments, net farm income this year would fall nearly 12% to $109.1 billion, according to agency data,” Huffstutter reported. “‘Government payments are doing a lot of the work in supporting crop producers,’ said Wesley Davis, a partner at Meridian Agribusiness Advisors, an agricultural economics consultancy in New York City.”

“Many farmers are increasingly dependent on federal support to pay their bills – while also taking on record levels of debt – even as government payments near record levels, economists said,” according to Huffstutter’s reporting. “USDA forecast that producers will receive $30.5 billion in direct payment support in 2025 and $44.3 billion in 2026, excluding additional payouts from federal crop insurance indemnities. Such levels have not been seen since 2020 and 2021 amid COVID-19 pandemic upheaval and trade disruptions during President Donald Trump’s first term.”

2026 Farm Income Forecast Details

Progressive Farmer’s Chris Clayton reported that “cash receipts for crop producers will be slightly higher until inflation is factored in. Crop cash receipts are forecast at $240.8 billion in 2026, an increase of $2.8 billion, or 1.2% higher than 2025 in nominal terms. USDA also noted, ‘However, the 2026 forecast represents a decline in real inflation-adjusted terms.'”

“Corn receipts are expected to grow $2 billion, or 3.3%, in 2026 to $63.67 billion, mainly due to higher quantities sold, given corn farmers produced a projected 17-billion-bushel (bb) crop last fall. Soybean receipts are expected to remain at prior year levels in 2026 at $44.5 billion,” Clayton reported. “But wheat receipts are projected to fall to $200 million or 2.4%, or $9.5 billion, due to lower quantities sold.”

“While the prices of cattle and calves are projected to grow again, USDA projects total animal/animal product cash receipts are forecast at $273.9 billion in 2026, a decrease of $17 billion, or about 5.8% in nominal terms from 2025,” Clayton reported. “Falling receipts for chicken eggs and milk, due to lower prices, are expected to drive the overall decline.”

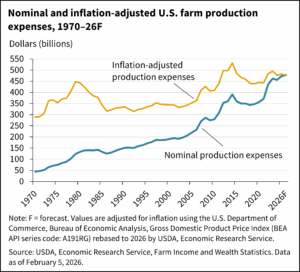

“Despite significant concerns raised by crop producers over production costs, USDA actually forecasts a slight decline when adjusted for inflation,” Clayton reported. “USDA forecasts farm sector production expenses at $477.7 billion in 2026, up from the 2025 forecast of $473.1 billion — an increase of $4.6 billion, or 1%, in nominal terms. When adjusted for inflation, USDA stated the expenses are projected to decline by $4.5 billion (0.9%) from their 2025 levels.”

Agri-Pulse’s Philip Brasher reported that “off-farm income will continue to keep farm households afloat this year, according to the forecast. The median total farm household income is projected to increase to $113,031 in 2026, a 2.7% increase from 2025. But the median farm income for farm households is forecast at a negative $1,161 this year, only slightly better than the median loss of $1,498 in 2025.”

USDA Also Slashes 2025 Farm Income Numbers

The American Farm Bureau Federation’s Daniel Munch and Faith Parum reported that “because USDA did not release its customary December farm income update, this February report marks the first update since September, and the changes are substantial.”

“USDA now estimates that 2025 net farm income totaled about $154.6 billion, down roughly $25 billion from the $179.8 billion forecast in September. Net cash farm income for 2025 was similarly revised down to about $153.9 billion, nearly $27 billion below the $180.7 billion previously projected,” Munch and Parum reported. “At the same time, USDA revised 2025 production expenses higher, to $473.1 billion, while adjusting direct government payments lower, to about $30.5 billion, roughly $10 billion below earlier expectations.”

“Together, these revisions suggest the farm economy is experiencing a generational downturn rather than a temporary slowdown. Outside of the cattle sector, most commodity markets are weakening,” Munch and Parum reported. “The updated forecast further cements that the expectations of a strong income rebound for 2025 did not come to fruition and this reinforces that farm profitability last year was more fragile than previously believed.”