Agriculture Secretary Brooke Rollins said on Tuesday that the Trump administration will announce a 'bridge payment' for farmers next week that is designed to provide short-term relief while longer trade…

Despite Some Alarming Signs, Repeat of 1980’s Farm Crisis Seen as Unlikely

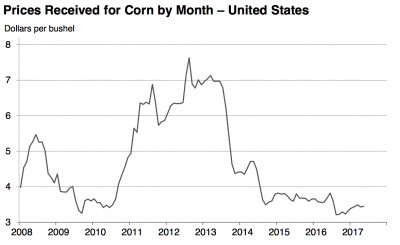

In the spring edition of the Agricultural Policy Review, Iowa State University agricultural economist Wendong Zhang penned an article titled, “Four Reasons Why We Aren’t Likely to See a Replay of the 1980’s Farm Crisis,” where he explained that, “There are plenty of alarming signs indicating a possible farm crisis: current corn prices are half the 2013 peak level of US $7/bushel; farm income has declined for major commodities (corn, wheat, cattle), falling from the previous year to levels well below recent years; weak farm income and worsening credit conditions continue to trim farmland values, which are expected to trend lower in the months ahead, thus weakening the equity position of producers and the collateral value for lenders. Given the heightening farm financial crisis, many agricultural lenders, academics, and other stakeholders in the US farm sector worry another farm crisis is looming. However, there are four economic and legal reasons why this farm downturn is unlikely to slide into a sudden collapse of agricultural markets.”

Dr. Zhang’s first reason for not seeing a sudden 1980’s slide is due to a “much stronger, real income accumulation before the current downturn.”

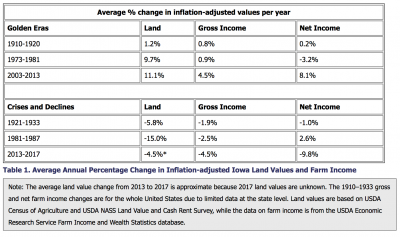

The Ag Policy Review article noted that, “Table 1 presents the average annual percentage change in inflation-adjusted Iowa land values, gross and net farm income for the three golden eras, and farm downturns. While it is concerning to see that since 2013 gross and net cash income has decreased 4.5 percent and 9.8 percent per year, respectively, it is equally important to note that from 2003 to 2013, gross and net income consistently grew 4.5 percent and 8.1 percent every year, reaching almost record-high levels in both farm income and land values.”

The update stated that:

A comparison between this third golden era and the two previous reveal that farmers accumulated much more income, especially cash, during the most recent decade than during the 1910s and 1970s before those farm crises.

Secondly, Dr. Zhang pointed to “historically low interest rates,” in support of his proposition.

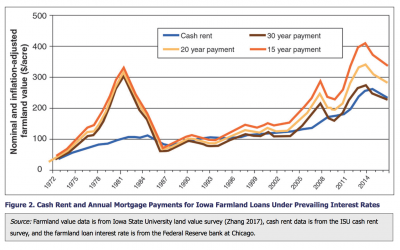

“Figure 2 [below] specifically compares the average cash rent and annual mortgage payments per acre for a typical Iowa farmland loan under prevailing farmland loan interest rates and varying terms,” the article said; and explained that, “It shows that due to abnormally high interest rates in the 1980s, the mortgage payment for a typical farmland loan was almost three times higher than the typical cash rent, and extending the farmland loan repayment schedules from 15 to 30 years did almost nothing to alleviate the financial burden faced by landowners.”

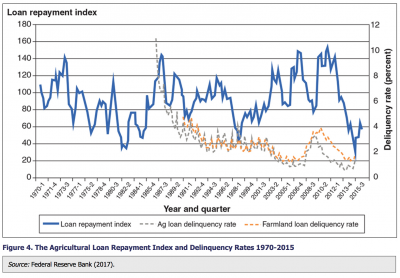

“More prudent agricultural lending in part driven by more stringent regulations,” is the third reason cited as a key difference from the environment of the 80’s.

Dr. Zhang indicated that,

After the 1980s farm crisis, the regulations on agricultural lending limits got tighter, and agricultural banks reverted to a 65 percent loan-to-value ratio, which became an even more stringent 50 percent loan-to-value ratio after the 2007–2008 financial crisis.

“Nowadays, one more factor helps limit the amount of debt and leverage faced by the US agricultural sector—collateral value is often calculated using a cash flow approach, as opposed to inflated market value. For example, in 2012 even though corn prices are approaching $7/bushel, the long-term average price of $4/bushel is often used by lenders like Farm Credit Service in calculating collateral value.”

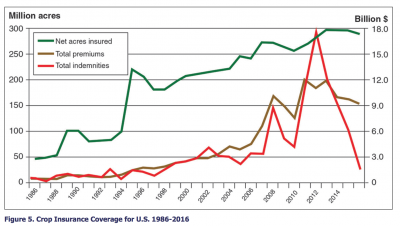

Lastly, the Ag Policy Review article indicated that a “stronger government safety net,” and in particular crop insurance participation, is a variable that is significantly different than the 1980’s.

“It is very important to point out the strength of the agricultural safety net—in 1987, only 50 million acres in the entire United States were insured in the Federal Crop Insurance program. Today, just the total cropland insured in Iowa exceeds 25 million acres, representing 93% of Iowa’s corn and soybean production acres.”

In conclusion, Dr. Zhang stated that, “Despite the deteriorating agricultural financial conditions and continued decline in farm income, the current farm downturn is more likely a liquidity and working capital problem, as opposed to a solvency and balance sheet problem for the entire agricultural sector. Rather than an abrupt farm crisis, we are likely experiencing a gradual, drawn-out downward adjustment to the historical normal return levels for the agricultural economy.”